| IV The Seventeenth Century. Virginal Literature and Church Music | CONTENTS | VI The “Verbunkos”. The National Musical Style of the Nineteenth Century |

{45.} V

The Eighteenth Century.

Song and Choir Literature

School music played an early role in the history of Hungarian music. From the sixteenth century onwards regular singing tuition as a secular subject was given in several Hungarian schools, and after 1680 there were repeated indications in school dramas of choirs and instruments. The indications of tunes in a number of plays point to them being sung. However the most conspicuous results of school musical tuition were achieved in the Calvinist colleges of the eighteenth century. The youth of the Hungarian lesser nobility were educated in these colleges, and this stratum of the population had brought along from the village residences, where the lesser nobility and serfs led a common life, a popular or popular-like melodic treasure. The old Calvinist colleges, Sárospatak, Debrecen, Pápa, Székelyudvarhely, Kolozsvár, Miskolc, Nagykőrös etc., became the collectors and organizers of this popular melodic culture by organizing (between the years of 1728 and 1811) regular school choirs, and participating officially in every principal urban or provincial burial and festive gathering. The metrical psalm-paraphrases of Buchanan and Olthof were already regularly sung at Sárospatak in the first half of the seventeenth century, and from 1728 onwards the choir made a regular appearance at burials with music. Singing technique in colleges received immense stimulation from the practice of polyphony that rapidly gained ground after the middle of the eighteenth century in Calvinist schools. György Maróthi, teacher at the college of Debrecen (1715–44), an outstanding pedagogue with a European outlook who returned from Swiss and Dutch universities with plans of radical reforms, drew up the first Hungarian compendia of musical theory in 1740 and 1743, and published Goudimel’s French psalm book for four voices in 1743 (on the basis of the simpler version from 1565) in Hungarian, with Albert Szenczi Molnár’s texts. This publication rapidly became popular, and the old Western choir-technique that entrusts the melody to the tenor of the four-part ensemble was a series of similar four-part adaptations of Hungarian folk songs or student songs between {46.} the years 1780 and 1820. The four regular voices were extended at Sárospatak around 1790 or even earlier, by the interweaving of new accessory voices (accantus, concantus, subcantus) into eight voices, and partly in this way, but also by the systematic transposition into a lower pitch of the discant voice, they produced a new, special form of choral design, related to the technique of the medieval organum and fauxbourdon. With this new practice, explained and discussed in several manuscripts of theoretical notebooks, polyphonic Hungarian choral literature arrived at the first stage on the difficult path of the first experiments.

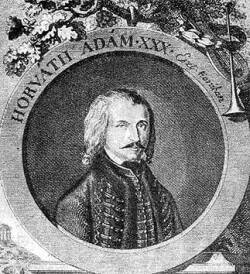

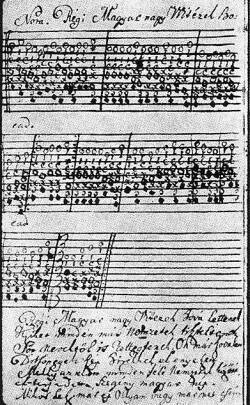

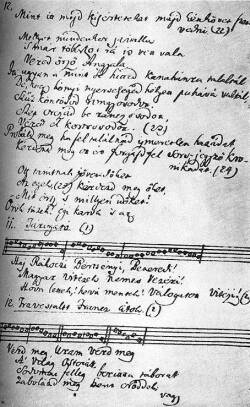

In addition to polyphonic applications, however, there was a homophonic song literature, the record of which survived in the students’ song-books, the melodiaria (song collections) of the eighteenth-nineteenth {47.} century. Their notation was still primitive and scanty, just as that of the biggest and most significant song collection of the period, Ádám Pálóczi Horváth’s Ötödfélszáz Énekek (Four hundred and fifty songs, compiled in 1813, published in 1853, containing 357 melodies). However, the surviving musical material was of epoch-making importance in spite of these deficiencies. First of all it showed that this period, the middle and the second half of the eighteenth century, was the time of the slow dying out of the old Hungarian melodic teasure and of the development of a new folk and popular melodic world. Indeed the new Hungarian folk-song style, as a forceful summing up of old, sporadic experiments, made its decisive appearance at this time, to rise in the course of coming decades to a crucial height in Hungarian and neighbouring folk music. The great social changes of this time were reflected in the increasing unfolding of the forceful style of the Hungarian folk song. These changes were caused by uprisings, changes of settlements and wanderings, as well as the {48.} breaking up of serfdom, the mixing of strata of the population and of old and new nationalities. How did these melodies reach the country houses of the nobility, and in what way did the fragments of “Kuruc” songs appear together with the new folk songs? As mentioned before, the poorer section of the lesser nobility lived more or less the same lives as their serfs, and in addition was prompted consciously by its oppositionary sentiments to look for a hold not only in everything that was “popular” but that was “ancient” as well. As is well known, the Hungarian lesser nobility, at the time of Empress Maria Theresa and of Emperor Joseph II, was mostly of oppositionary and “Kuruc” sentiments, and this spirit made them unconsciously look to the past also in its musical interests. It had carefully preserved the memories of Thököly’s {50.} and Rákóczi’s era and this may well explain why we find the first recorders of the “Kuruc” melodies among the lesser nobility. These “melodiaria” show also that Hungarian song, inspired and enriched by West European examples, reached the first phase of its formal perfection in the scholastic music of the eighteenth century. The ancient melodiousness, conceived in the spirit of homophonous, pentatonic or church modes, was dying out and the new Hungarian song literature of the eighteenth century, full of delicate nuances and minute details, built up on the Western major and minor system, was taking its place.

Almost at the same time another tendency appeared in the history of Hungarian song literature. The pioneers of this tendency preached complete association with Europe. They did not believe that national art can grow only from deeper, native roots, and ailing a developed musical culture in Hungary, such as they had so mufch admired in Italy and Germany, they came to the conclusion that the best solution would be the simple adaptation of what had been done there. Some of these pioneers tried to popularize the selected products of the Viennese song style by furnishing them with Hungarian texts, while others attempted to compose songs in the sytle of the “gallant” German and Italian song literature. The poet Baron László Amadé (1703–1764) was probably the first to inspire this Western school, while the novelist Ignác Mészáros could be called its founder. Its most important and conscious representative was Ferenc Verseghy, poet, writer and linguist (1757–1882). The Western school gave the impulse to a movement lasting for more than a century, and it can perhaps be said that its influence is still felt today. The gently graceful melodies of Western character, imported from Germany and introduced into Hungarian poetry and music on Amadé’s, Mészáros’s and Verseghy’ initiative, had to be altered radically or even to disappear completely, for they had been written according to the laws, to the prosody, the structure, of another language. But their influence proved to be of a more abiding value in the acclimatization of the prosody of German-Italian character and the Western melody pattern. The Germanophile composers of the nineteenth century working in Hungary, who had turned for direct examples and inspiration to Mozart and Schubert and later on to Schumann or {51.} Wagner, had their roots in the movement, and, to some extent inherited the enthusiastic Europeanism and thirst for Western culture of Verseghy and his circle. As for their formal technique and idiom, they remained, practically through the entire nineteenth century, the authoritative and leading composers, and were problably regarded by the untutored “Magyar” artists with awe and aversion. Verseghy’s most impressive compendia were made between 1780 and 1807 [among them the Rövid értekezése a musikáról (Short treatises on music), 1791, Magyar Aglája (Hungarian Aglája), 1806, Magyar Hárfás (Hungarian Harpist), 1807]. Viennese music, the music of Haydn, Steffan and their contemporaries prevail in all of them, while the attempts at the Hungarian song or at the stylized folk song played a subordinate role. The melody, the “aria” was, in comparison with the text, of predominant importance (“it is more advisable to write words to arias, than arias to words”) and it is strange that Pálóczi Horváth, who was a determined opposer of Western orientation, should have turned to the principles of the “Germanophile school”, by urging the superiority of the melody (1787). The ideal of melodiousness was always represented by the Western melody, and not by “the tunes wanting in rhythm and measure,” within reach of Verseghy and his circle, “the religious or secular sing-song of our country folk and those symphonies or rather dysphonies, aped as a rule by our Gipsies in such a miserable manner”.

The third melodic style at the end of the eighteenth century, the literature of vocally performed dance tunes, originated essentially from the same principle – the superiority of the melody and the subordination of the text. The vocal performance turns at this point into the propagative instrument of a new musical movement, of the conquering fashion of “verbunkos”. Its cultivators became the heralds of the new Hungarian music by writing texts to melodies of instrumental character, and by ignoring the fact that the peculiar figuration of dance pieces was contradictory at every step to the demands of the singing voice. The fashion of vocal “verbunkos”, in spite of all the inner contradictions of the genre, lasted well into the nineteenth century, and may be felt practically up to the present time. This melodic style, however, only faintly reflected the process, taking place in the meantime {52.} in another sphere of musical life. The popular song literature of the nineteenth century was undoubtedly the descendant of the song literature of colleges, its “western”, “Germanized”, “urban” tunes may be regarded as the continuation of the movement initiated by Verseghy’s circle. The fashion of vocal dance pieces, however, made its appearance, and subsequently faded away, together with the new music, the “verbunkos”, that rose to national predominance at the end of the eighteenth century. The picture of the entire Hungarian musical culture was changed at the same time.

| IV The Seventeenth Century. Virginal Literature and Church Music | CONTENTS | VI The “Verbunkos”. The National Musical Style of the Nineteenth Century |