| Hair and Headdress | CONTENTS | Outer Wear |

Underwear

Underwear is usually made out of linen, more recently replaced with cambric (gyolcs) for Sunday wear, the Hungarian name evoking the name of the German town, Cologne. Most of the articles of clothing were of linen, as was much of women’s outer clothing until recently. This is the reason why women are called white servants, linen servants, and white folk all over the country. Clothing made of flax or hemp linen used to be worn as outer garments during the summer, and as underwear in winter, with another garment worn over it.

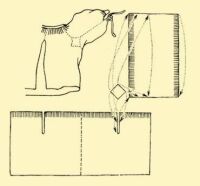

Lóc, Nógrád County. Early 20th century

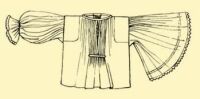

The most important piece of underwear is the blouse or chemise, which is found in both a long and short version. The cut may be either with the sleeves gathered into the neck or with the sleeves sewn on to the shoulders. The short blouse or shift, which evokes Renaissance tradition, reaches past the waist just far enough to be held to the body by tying the skirt over it. The chemise covers the body to mid-calf. In the case of the first type of blouse, the sleeves were inserted directly into the collar, thus making it possible to gather the shirt’s front. This style was still popular during the last century but gradually was replaced by the second type of blouse having sleeves sewn to the shoulders. Blouses function equally as under or outer garments. The front, cuffs, and shoulder sections may be richly ornamented, especially for young people and in certain regions (Kalotaszeg and Sárköz).

Palotsland. Early 20th century

Women wear a petticoat called pendely with the short-waisted blouse, which surrounds the lower part of the body like a skirt. The blouse and petticoat were often sewn together, and this is how the chemise came into being. If the petticoat is worn as underwear, it is unseemly to let it be seen under the outer garment, but if it is used as an outer garment, it is treated as such. In such cases they pleated it carefully and even ornamented it in various ways.

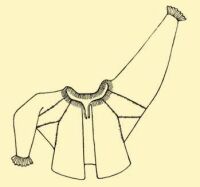

Martos, former Komárom County. 1930s

Men’s shirts can also be long or short, the latter, found especially in the Great Plain, are even shorter than the waist. The shirt of the bridegroom played an important role at weddings. It was made at the bride’s house and carried in procession to the bridegroom, who wore it at the wedding. Although he might put it on again occasionally, he would preserve his festive shirt for his funeral. There was no collar on the oldest type of shirts, only a band or binding was sewn around the neck. The shirt with a folded collar is a newcomer, appearing at the end of the last century, and in many places is called “soldier’s shirt” (katonaing), indicating its origin. As cambric was becoming more popular than linen, this type of shirt became extremely loose-fitting. The gathered sleeves were sewn into the shoulders of shirts called borjúszájú ing or lobogós ujjú ing (shirts with very wide sleeves). In the case of shirts with sleeves gathered into a cuff, which appear to be newer in origin, the lower part of the sleeve is gathered. The front and the cuffs of men’s shirts were embroidered in some places with white-work (Somogy, {323.} Nógrád, and Tolna Counties) or colourful needlework (e.g. Matyóföld, Kalotaszeg). The material used for shirts is always white; only the horseherdsmen of the Hortobágy wear dark blue shirts. Although a man’s shirt is considered an undergarment, it is used as an outer garment in many places, especially in regions where its ornamentation especially justifies it as such.

The men’s undergarment, the gatya, a long pantaloon, was made of white linen. In some places the edges were trimmed with fringes and occasionally they were ornamented with embroidery (Transdanubia). This piece of clothing, like the petticoat, could also function as both an under and outer garment. During the 19th century a double pair of gatya were worn during the winter, one over the other. The linen gatya was changed regularly, but if two were worn, they dipped the upper one in ashy water, smeared it with lard and bacon ring, and wore it until it fell apart. A wider variation of the gatya, the bőgatya, appeared as an outer garment with the adaptation of cambric. The more widths of cambric that went into its cutting, the more handsome it was considered to be. These gatyas were worn only on festive occasions along with the widesleeved shirt.

| Hair and Headdress | CONTENTS | Outer Wear |