| Homespun | CONTENTS | Pottery |

Embroideries

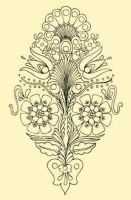

Embroidery is one of the richest, most diverse branches of Hungarian ornamental folk art, and is extremely varied within a relatively small area. We can divide embroideries into two groups. One of these stands very close to woven textiles and is made by sewing the pattern into the plain homespun by counting threads. That is precisely why the elements {396.} of such cross and oblique cross-stitch embroidery (keresztszemes, szálánvarrott hímzés) are geometric, so that the insufficiently practised eye can easily confuse this form of embroidery with weavings. In contradiction to this, the freely drawn embroidery (szabadrajzú hímzés) is only slightly restricted by the basic material, so that it provides greater opportunity for variation of both the traditional and spontaneous elements.

General

Even little girls attempt to embroider, although the really good embroiderer is the one who is able to expertly vary and create new forms using the old wealth of motifs. Such women often become specialists who sometimes make the entire trousseau of marriageable girls in return for smaller or larger recompensation. The importance of the drawing women (íróasszonyok), who draw the most beautiful designs on the basic material that are brought to them, is especially great in the case of freely-drawn embroideries, so that women possessing less talent and practice can venture to embroider their designs.

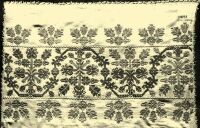

Szirma, Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County

Both ceremonial and plain pieces for everyday use were embroidered. That is why needlework has a great role, primarily on the visible parts of various folk costumes. The same can be said of pillow ends (párnavég), which are placed on the end of the pillow facing outwards on the bed, {397.} their ornament outwards, as well as of the various kerchiefs, covers, tablecloths, and towels, so that the embroidered flowers may please not only the family but visitors as well. However, no matter how ornate these objects are, they all have some kind of a definite function.

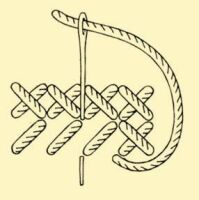

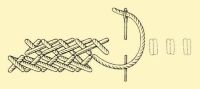

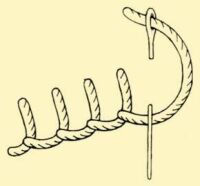

Handwoven homespun or purchased linen of a later period provided the basic material for embroidery, while the yarn for needlework was either dyed at home with plant dyes or, in some areas, bought from merchants. Among the various stitches the previously-mentioned cross stitch, in which two or more stitches are placed cross-wise to create a handwoven effect, is related to the geometric designs. One of its versions is the oblique chain stitch embroidery, which makes the embroidering of certain freer patterns possible. In this case two tiny squares are sewn with three stitches instead of four. Several versions of the satin stitch (laposöltés) are known over the Hungarian linguistic region, depending on whether the threads line up partially or completely next to each other. This is the most widely spread technique of Hungarian embroidery. The common character of loop and chain stitch (hurok- and láncöltés) is that a loop is formed on the face of the material. The various methods of fastening this down assure the different characters of the embroideries.

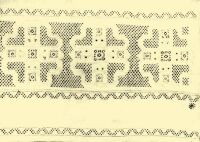

Various principles prevail in Hungarian embroideries, not only in technique, but in the composition of the stitches as well. However, the most general and most classic is the three-part division. According to this, the main motif, stretched in a longitudinal direction, is placed in the centre of the surface to be ornamented. This motif is closed off at the top and at the bottom by a border, the so-called mesterke, narrower than the former, and mostly open towards the linen. This mesterke contains the oldest design elements, which were slowly pushed out to the edges.

In some cases, embroidery was done by the men as well; these were always artisans who, besides tailoring and sewing certain outer garments, also decorated them.

Veszprém County. Early 19th century

The material of the ornamental mantle (cifraszűr) is white or whitish rough broadcloth, which was embroidered with black and red wool or silk yarn, in some places with blue or even yellow. The designs, the most frequent basic element of which are the rose, carnation, tulip, and lily-of-the-valley, and the leaves that surround them, got onto the szűr during the last two hundred years. The work of ornamentation is called “flowering” (virágozás) by the mantle makers, and the flower bouquet growing out of baskets and pots gave the inducement to its composition. Immoderate ornamentation became preponderant on mantle {398.} from the middle of the last century. As far as possible, the embroiderer left no empty areas on the visible surfaces.

Region along the river Ipoly, Nógrád County. Early 20th century

The most ornamental mantles were made in Eger with embroidered flowers covering the whole garment. In the Hajdúság they primarily embroider its two sides, the so-called aszaj, while the mantles of the Kunság can be recognized from their wreath motifs. Black appliqué designs are sewn on the mantles in the region east of the Tisza, chiefly in Bihar County, a practice which gained ground especially with the spread of sewing machines. This type of szűr even found its way to some places in Transylvania, such as Kalotaszeg (cf. p. 325). The mantles of Bakony and Somogy are not only distinguishable by their shortness, but also by their special world of design, in which, among other things, red appliqué also figures. This was even worn by the nobility in the middle of the last century as a sign of national resistance; furthermore they wore it when they went to the aid of the Italians in their war of liberation. That is why one version is called the Garibaldi szűr.

Veszprém County

The embroidery of sheepskin garments along the seams (cf. also p. 332), is closely related to the embroidery on mantles. Such garments can still be found in many places, but really beautiful examples have survived primarily in Transylvania. They used furrier’s silk, less frequently wool, to embroider the rich flower patterns with satin stitch. From the end of the 18th century various flower motifs, tied into bouquets, began to appear in increasingly stylized forms as on the mantles. Certain differences in colour are apparent in the various parts of the linguistic territory. Thus in Kalotaszeg variations of the red colours dominate; they wore similar garments along the Homoród of Székelyland. Sheepskin garments were rarely ornamented in Csík; at most a bit of embroidery appears along the seam. The most ornamented are the jackets or ködmön of the Great Plain, the ones of Békés County standing out even among these, perhaps because here the influences of various nationalities met with those of the Hungarians (cf. Plate XXXVII). The short sheepskin mantles of the Hajdúság are embroidered mostly with black and the cloaks (suba) of Jászság with green. Between the Danube {399.} and the Tisza the Calvinists preferred a red colour scheme, while the Catholics preferred shades of blue and yellow. The ködmön of Transdanubia was embroidered with red, although other coloured yarns were also used in certain places.

Embroidery on linen was always done by women. Needlework is so varied over the different parts of the linguistic territory that we can undertake the introduction of only a few more characteristic and general versions.

One of the oldest known comes from the Great Plain, more specifically from Nagykunság, Hódmezővásárhely, and Orosháza, and is crewel-work called szőrhímzés (cf. Plates XXXIV, XXXVI). Such work was carried out with satin stitch, using woollen yarn in fine shades of blue, green, and red. Sometimes black was also used. The rose surrounded by flowers and leaves is the most popular motif, but tulips are also frequent. Similar designs have turned up recently from Transdanubia and Upper Hungary, evidence suggesting that their proliferation at one time may have been general.

Zala County

On the embroidery of Rábaköz, we often find freely-drawn work alongside the cross stitch and laid stitch needlework (cf. Plate XXXV). Usually such cross stitch work was embroidered with red yarn and the pattern was fringed with small spiral lines. Flower motifs prevail primarily among the freely-drawn work, although sometimes birds also occur. In this type we often feel the influence of historical styles. Such embroidery has not been made for a long time, and can be studied only on museum pieces. A delicate kind of white embroidery {400.} can be found around Kapuvár, principally in Hövej. Mainly head kerchiefs were ornamented with this type of work.

White embroideries form a separate group of their own, which are known in many places, or at least used to be known in the recent past. Some of these are related to button-hole embroidery. Such may be found in Somogy, Zala and Veszprém counties, where this needlework primarily adorned young men’s shirts, especially those the bride gave the groom. The embroidery of Tura was also white originally, and cloths for food carrying, as well as shoulder-, head-, and handkerchiefs were decorated with it. The small flowers have become colourful and have grown in size during an observably short time, and along with the change in their composition, have also loosened up. This colourful type of satin-stitch embroidery then spread to the neighbouring villages.

The process of increased colouring is general among those embroideries that still exist today in the hands of the peasantry. Kalocsa and its surroundings give us the best examples. These originated from the factory-produced button-hole embroidery of the end of the last century, which the peasants began to imitate in red, blue, and black colours. During the last decades colouring has developed further, and today twenty-two shades of colour are used on the bodices, aprons, headdresses, and more recently on kerchiefs and coverings. The drawing women depart farther and farther away from the original patterns, and design richly ornamented, flowery, leafy, sarmentous patterns. This folk art did not stop at embroidery, but expanded to the painting of furniture, {401.} the walls of houses, and recently even to decorating Easter eggs and painting flowers on plates.

Region of Sárköz, Tolna County. Early 20th century

The people of Sárköz are outstanding masters not only of weaving but also of embroidery. The motifs of the red or black pillows to be put under the head of a corpse are connected with the Renaissance embroideries of the 16th and 17th centuries. Best known are headdresses embroidered in white on a black background. First the surface to be ornamented is outlined, then filled in richly, impromptu, without predrawing. Flowers, leaves, branches, even stylized birds, although less frequently, occurred in their patterns. Not everybody ventured to make the really ornate pieces, so women purchased or ordered the ones that suited their hearts’ desire from outstanding sewing women (varróasszonyok). Young wives, called menyecske in Hungarian, wrapped a veil, the so-called bíbor, made out of voile, over their headdresses. Not only was the border of such a veil embroidered richly, but it was also embellished with metal sequins. It seems that this fashion came to the Sárköz district along the Danube from the Croatians and Serbians.

Sárköz

Region of Kalotaszeg. Early 20th century

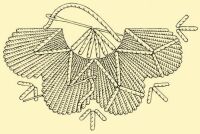

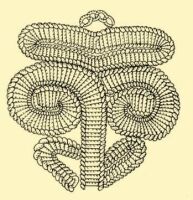

Matyó embroidery, in its present form, is fairly new in origin. The earlier designs were red and blue coloured cross stitched work, but the basic motif of even these was floral adapted to a geometric technique. A version of this form of embroidery exists to this day in Tard. Much more general, already in the last century, was the type of freely-drawn embroidery, the basic motif of which is a rose and leaves attached to it (cf. Plate XXXVIII). Earlier the colour was also red and blue, and such {402.} needlework was used to decorate the ends of sheets, pillows, and certain garments of men’s wear. Since the turn of the century this embroidery became so densely worked with multi-coloured silk and wool yarn, that the basic material was completely covered with the roses and leaves. These compositions, drawn by the most outstanding “writing women” (íróasszonyok), often resemble the ornamentation of furriers. Long after the furriers had stopped doing such work, drawing women still continued to sew old and new variations of their wealth of patterns.

Mezőkövesd

Kalotaszeg region, former Kolozs County

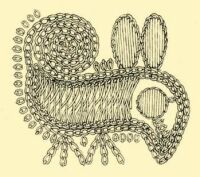

The kalotaszegi írásos (“written” or pre-printed embroidery of Kalotaszeg) is one of the best known embroideries of Transylvania. Using a goose feather or the tip of the spindle dipped in a mixture of milk and soot, women draw the designs on the linen without any previous division of space, yet in such a way that it fits the given area exactly. The outlines were made by old women in whose heads and hands innumerable variations of the wealth of patterns existed. They ornamented sheets, pillowcases, coverings, and towels in this way. An increasing density in the pattern can be observed to have evolved here also; and not only was the closed square chain stitch used, but also the satin stitch to fill the left out areas. The most frequent colour of this work is red, but black {404.} and dark blue also occur, usually just one or the other, because formerly such embroidery was always done in only one colour. The oldest írásos embroideries of Kalotaszeg still bore traces of the rigidity of their geometric ancestors, but at other times they evoke flower compositions, which through the mediation of the Renaissance can be traced to Italy.

Kalotaszeg region, former Kolozs County

Kalotaszeg region, former Kolozs County

Besides the freely pre-drawn type, the significant majority of embroideries in Székelyland are oblique chain stitch (szálán varrott) embroidery. Its ornamental elements have scarcely departed from those of the handwoven textiles. Often woven and embroidered pillowcases for marriageable girls are made with the same motifs. In the region of Kászon we can find almost all variations of the Székely oblique chain stitch embroidery. Their construction is well arranged and proportioned. The wide central motif that stretches in the middle gives the name to the different embroideries. They may call patterns various names, such as large plate, big or dense stars, dense rose, table leg, big apple, cockscomb, and wide stripe. These are borders on top and bottom of the central band, the so-called mesterke. In case of the oblique cross stitch embroideries of Székelyland, the two mesterkes together are not wider than one third or one half of the central band. Originally these {405.} patterns were worked with red yarn, but later blue, and at some places even black appeared. In many cases the designs show a relationship to the embroidery of the Saxons; in origin they can be traced back all the way to the Middle Ages.

Former Háromszék County

We have already mentioned macramé fringe tying as one form of lace making (csipkeverés). The ornamental way of sewing together two widths of linen into either a sheet, a covering, or a tablecloth, can be compared to such work. However, we cannot really speak here of expressly Hungarian peasant lace making. This does not mean that lace {406.} was not used; it was, but the lace was made by the Slovaks and the Saxons of Upper Hungary, and was sold on the greater part of the Hungarian linguistic region by wandering merchants. At the turn of the century, there were several attempts to adapt lace-making, but this succeeded only at Kiskunhalas and Karcag. The lace made here is enjoying great popularity to this day, both at home and abroad.

| Homespun | CONTENTS | Pottery |