| Pottery | CONTENTS | III. Cultural Anthropology |

Other Branches of Ornamental Folk Art

Besides the main and most general branches, there are several kinds of Hungarian ornamental folk art that are worth mentioning briefly.

The extraordinarily rich metal art of the conquering Magyars barely left an impression on ornamental folk art in metal of the near past. We can even say that this branch of Hungarian ornamental folk art is relatively poor compared to the others, and it also did not participate in the great revival of the last century.

Palotsland. Early 20th century

Peasant craftsmen are able to do certain types of metal ornamentation, and as we have seen, in some places the wood-carving herdsmen also apply metal. However, it is essentially still artisans, above all blacksmiths and locksmiths, who understand this branch of art best. A significant portion are Hungarian, but there are also a great many Gypsies among them, and excellent works of art are turned out of their hands. The Gypsies, who moved to Hungary during the Middle Ages, live scattered through the entire Carpathian Basin and pursue many different occupations. Thus there are among them musicians, wood carvers, trough carvers, reed makers for the loom, reed and tape weavers, but their main trade is still that of blacksmith and locksmith. They made various iron objects and work implements according to the taste of the persons who ordered them, and where there was an opportunity, they also ornamented it.

The young peasant man not only carved the distaff (guzsaly) of his beloved richly with flowers, but primarily in Upper Hungary decorated it with lead or tin casting, which he poured into a pre-hollowed hole. The designs were mostly geometric, and some can be traced back to the Gothic wealth of patterns. The relatively few elements were varied in such a way that they never became monotonous. In Kalotaszeg even spindle-weights were cast at home into moulds made of wood or alabaster. Initially geometric designs were also carved into these, then they put the mould away and used it when it was needed.

The blacksmiths and locksmiths ornamented even the simplest tools. Actually the brand mark is an elementary form of this practice and was used by its maker on the haycutter, vine pruning knife, and, less {418.} frequently, even on the plough share. It might be a star, a roughly sketched heart, cross, half-moon, or a primitive flower consisting only of a few lines. But they also applied richer ornamentation by chiselling and punching. Sometimes we even find sarmentous floral motifs. The best blacksmiths decorated hatchets with copper or other metal inlay.

Balmazújváros, former Hajdú County. 1908

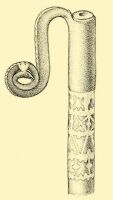

Blacksmiths also made objects which were first cast, then decorated, such as brass buckles. Some of these were used to fasten a bell to the leather strapped around the neck of oxen. An old, popular motif on such buckles is a pair of birds looking in opposite directions, though other animals were also frequently represented. After casting, the metal surface was refined and ivy, flower, linear or dotted ornamentation was applied. Of the moulds the most beautiful are the shepherd’s crooks, made of brass, the outer loops of which were decorated with snake’s heads, stars, and flowers. The smooth surfaces were decorated with metal buttons or incised with leaf and branch designs. Smaller and larger bells were made the same way, except that their decoration was only incised.

Kecskemét, Bács-Kiskun County. 19th century

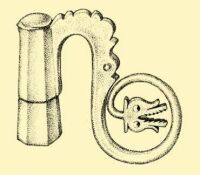

Blacksmiths also made objects which, though they had a function, still for the most part counted as ornaments. Such are the distaff nail (guzsalyszeg) and distaff pin (guzsalytű), with which they fasten the tow onto the distaff. The head of the nail gives an opportunity for embellishment, but the bottom was not altered because that was used to fulfil the original function. Hoops, leaves and squares were added on its upper section, and stretched spirals on its two sides, which lent a bouquet appearance to the whole thing.

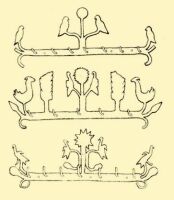

The blacksmith made coathangers and lid holders usually out of barrel hoops. He worked the metal cold. He cut small pieces off the hoop, straightened them with a hammer, then shaped a coathanger out of it. He either decorated its upper part with simple notching, or perhaps shaped it in the form of a leaf or a flower. Animal figures were often added, especially the confronting cock and bird. The finished coathanger or lid holder was cleaned thoroughly, then painted with different colours, and in this way it became a favourite colourful spot of the house.

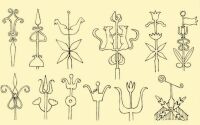

Ornaments made of wood or woven from straw were placed on the crest of the house in some places, but flowers made of wrought iron by the blacksmiths were considered the most beautiful. Although these can be found over the entire Hungarian linguistic region, the most superb pieces are known to us from the Great Plain. The star and half-moon motifs refer not only to the Calvinist religion of the inhabitants, but possibly to Turkish times. The ornamental cross is general among Catholics. Most crest-ornaments are flower shaped; thus tulips and carnations are the most frequent, but capitulum and pomegranates also occur. The majority of these iron ornaments carry a Renaissance heritage.

Besides beads, various pieces of metal jewellery–earrings, bracelets, necklaces, rings–also belonged to the Hungarian folk costume. Their makers are peasant silvermiths who congregated in certain larger cities such as Győr, Komárom, and Baja, and supplied huge areas from here. They worked mostly from silver, which they bought relatively cheaply; they also used silver coins, either melted down or with some transformation. {419.} Their designs are usually based on flowers and plants, and so clovers, six to eight petalled flowers and lentils appear among the patterns, while certain designs are named a shell, a star, or a butterfly. These peasant silversmiths worked until the most recent times, especially in the southern part of the linguistic territory.

Hódmezővásárhely, Csongrád County. Early 20th century

Horsehair work is relatively rare; its masters are primarily men who work with horses (horseherds, drivers). Earlier they wove many consumer items out of the strong, ductile, and almost unbreakable horsehair (halter, rope, whip, shackle, etc.), but there were also some items which served primarily as ornaments. Such is, for instance, the pinholder, the centre of which is made of wood, birdbone, or feather, and was richly braided with horsehair all around. They also made rings, necklaces, and earrings out of horsehair. The technique and artistic character of these objects is of such high grade that it surpasses the professional button makers’ lacings.

We have spoken of leather in several respects. The bootmakers ornamented women’s footwear in different ways, and we also became acquainted with the colourful embroideries and appliqués of furriers, but beside these, ornamental leather had many more functions. The harness maker is also a professional master of leather processing. The main part of his work consists of making richly ornamented saddlery. One of its most important elements is the ornamental fringe (sallang), made of leather and embellished in various ways. For example, they often saw red, yellow or green appliqué on black leather to emphasize the shape of the design. The edge of the harness formed into different shapes, and a whole composition created by cutting holes in it. There are also outstanding masters of weaving a flat braid out of thongs split very thin. These are fastened together with copper stars.

The distaff ribbons (guzsalyszalag) of the young Matyó wives and girls were ornamented mostly by the furriers. The women fastened the rolled-up tow with a string at the bottom, covering it with a leather strip embroidered in light brown, purple and light green. The strip widened towards the bottom and covered the top part of the tow entirely. It was decorated with circular, undulating rows of holes and its edges were laced. Such were given only by young men to young maidens.

Great Cumania (Nagykunság). 19th–20th century

Miske, Bács-Kiskun County

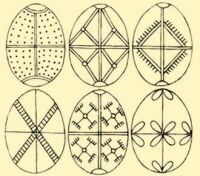

{420.} The painting of Easter eggs is a branch of ornamental folk art especially tied to beliefs and customs (cf. pp. 645–6). The egg, as a symbol of fertility, plays an important role among beliefs, but the giving of ornamental egg itself is tied to the Easter holidays. This custom is actively alive to this day, both in villages and in cities. The long history of egg painting is demonstrated by the fact that such an egg has been found in an Avar grave from the period of the migration. The same is proved by such elements of design as one version of the swastika, as well as by a rake-like motif, and by many other geometric patterns that survived only on the Easter eggs. These are called both ornamental eggs in reference to their decoration, and red eggs, in reference to their colour. Among the many methods of making them, the resist technique is most frequent. With the help of a quill a pattern of melted wax is dripped on the cooled egg, then the whole egg is coloured. Afterward the wax is wiped off and the pattern underneath remains white. They rub the egg with an oiled rag to make it shiny. Sometimes the design is etched on the dyed surface with a sharp instrument. People know how to do egg painting, just as they know how to embroider, in every house, but this art too has outstanding specialists, usually old women who, for a kind word, or perhaps for a few eggs, will happily do the work of decorating.

Ormánság region, Baranya County. 1950s

| Pottery | CONTENTS | III. Cultural Anthropology |