| On the History of Family Organization | CONTENTS | The Troop, Clan, Kindred |

Family Organization

We can best get acquainted with the family, and the extended family, by enumerating the rights, obligations and tasks of its members.

The head of the extended family is the gazda, who is the absolute and incontrovertible master of all members of the family. He was able to shut out members of the family from the unit. Usually the gazda was the oldest, most experienced member of the family, and if they lived in an extended large family, not his son, but usually his brother followed him after his death, based on seniority. This method of inheritance goes back to the distant past, occurring, for example, in the succession of the House of Árpád during the 11th to the 13th centuries.

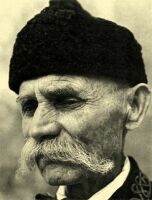

Szany, Győr-Sopron County

{57.} The gazda disposed of all the material goods of the family freely and without any obligation of accountability. Thus he could submit to sell both his inherited and acquired land, he could spend, drink up, or even give away its sale price, and he could do so without being called to account for it by members of the family. Although this happened only on rare occasions, we mention it simply to indicate the extent of the gazda’s unrestricted authority. The majority of the gazdas always strove to acquire more, either to buy fresh land or to gain parts of hitherto undivided fallow land. Thus in the age of serfdom the entire family cleared the forest, dried out swampy areas, and broke in pasture land, after which they did not have to pay ninth dues and tithes. From the middle of the 19th century the gazda tried to increase his property by acquiring the land of people financially ruined or dead. Although he asked the opinion of his grown and married sons at the time of purchase, their opinion did not change his decision.

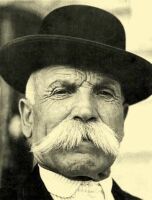

Great Plain

He alone disposed of all produce that grew on the land and even in the {58.} garden around the house. He separated what seemed to be sufficient for the year’s food from what he wanted to sell at the weekly market or at the fair. He kept the key of the granary always on himself, so that no one could enter without him. Similarly, he alone issued the wine and brandy, and he kept a strict note of the change in quantity. He kept all the money coming from various sources in a box that would lock well, or perhaps in an earthenware vessel, but we know of some who carried the money around their neck.

The basic expenditures of the large family were paid by the gazda. He also paid the different taxes, acquired and repaired the agricultural tools, and bought new stock. He was responsible only for the purchase of the major articles of clothing for the members of the family. Thus, boots, frieze mantles, coats, and later on shoes were bought at big fairs. But all gazdas tried to urge members of their household to make the greater part of their own clothes from flax, hemp, and, where possible, wool. Whatever went beyond that, the wife tried to juggle out of the price of {59.} milk, eggs, and chickens, although in many places the gazda tried to keep track even of this sum.

The gazda maintained the right to the income of the family not derived directly from his own property. Thus certain male members of even prosperous Palots families went down to the Great Plain to harvest. They brought back their share of crops and the family could bake milk loaves out of that for themselves all year. The gazda utilized the surplus working power of the extended joint family in other ways as well. He sent his sons to the forest for daywork where an opportunity was offered, or perhaps they undertook a haulage. The income from all this was at the command of the gazda, and at the most he gave some of it back to those who earned it. He provided smaller sums to his unmarried sons on Sunday, so they could go to the inn.

The gazda directed all the work on the property, although in this–especially during his later years–he did not physically participate in most cases. He decided who among his sons, sons-in-law, daughters and daughters-in-law would do what work on a certain day, and determined the quantity of the work. He himself usually worked around the house, repairing tools and buildings leisurely, so as not to tire himself out. He visited the fields only periodically to supervise the work. He took part in actual work mostly during harvesting and did hauling only if others in the family were doing some more urgent chores.

He also kept in his hand the formation of his family, thus determining, mostly on economic considerations, the marriage partners of his sons and daughters. He had the right to scold or even beat anyone within the family, although he did this to adults only in the most extreme cases. Primarily it was the children who suffered physical punishment. Although the village community debated abuses of patriarchal authority, no opinion of any kind whatsoever could effectively influence the father’s decision.

The gazda looked upon the sons’ introduction to work and other knowledge as his task, while his wife, the gazdasszony, saw to rearing the daughters, something the father did not concern himself with. A small boy usually rode on the cart so that he could get used to the road and horses; at the age of six he was already guarding the geese and the chickens against predators, at first in the yard and later in the pastures outside the village. A ten-year-old child was already hoeing, although it is true that he did only half a row and the adults did the rest of it for him. The father got his son used to the scythe by the age of fifteen. At first he cut fodder, then grass. They started him on grain harvesting (unless necessity brought it about otherwise) only after the age of eighteen, and until then he learned how to lay in swaths, and at some places how to bind and stack sheaves. The gazda always enjoyed working with his sons and even more with his grandsons; he told them tales and stories, and gave accounts of his experiences in soldiering. This is why songs, ballads, and tales descended from grandparents to grandchildren rather than from parents to children.

The gazda represented the family in negotiations with relatives and neighbours as well as before various village, state, and church bodies. A special place was due to him in church together with the other gazdas {60.} which was passed down to them through heredity. At the market he always disposed by himself of the produce, animals, and products that were to be sold, and in buying he at best asked advice only from the member of the family older than himself.

The few features listed above show that the authority of the head of the large family was made evident in every respect. This was also the case in the narrower nuclear family, with the difference that here a great deal more work fell to the share of the head of the family. The gazda was almost without exception that member of the family who possessed the widest range of knowledge. Generally, he tried to pass his knowledge on to his family. The best among them became the peasant leaders of the village, organizers of weddings and burials, and also represented the interests of the larger community.

The other prominent individual, who on the whole was totally subordinate to the gazda, is the gazdasszony. Generally she is the wife of the gazda, and only rarely did it happen that, after the death of the gazda, and if her son agreed to it, she continued to be gazdasszony. Her task was–with the help of her daughters and daughters-in-law–first of all to do the housework and the work around the house. She did not take much part in work in the field, at most she carried food out to the workers at the time of the big harvests.

Her most important task was cooking, as well as baking bread and processing the milk. All of this she would not let out of her hands as long as she was able, and usually she employed the help of the oldest menyecske (young wife). Raising and feeding the small stock was among her tasks along with accounting for eggs. She used the profit gained from milk and poultry for the clothing of the family. Out of it she also helped her daughter when she parted from the family and covered the trifling expenses of her grandchildren. She kept secret the amount of her income, for the gazda held it to belong to the common income.

The burden of clothing the family also lay on the gazdasszony’s shoulders. Thus the processing of hemp and flax, from pulling it out of the ground to the weaving of the homespun, counted as one of her most important tasks. From the prepared linen, the women sewed the undergarments, and in many cases the outer garments, of both men and women, but the gazdasszony also had to get together year by year the dowry of the girls growing to marriageable age. In areas where these tasks are still practised the number of her chores was increased by the processing of wool and even by the sewing of cloth garments. Naturally, keeping the house and washing was her burden too, as well as taking care of the vegetable garden and gathering, storing and preserving her produce–all of which meant a good deal of care.

At the same time the gazdasszony was also a mother, who held the rearing of her children to be one of her most important tasks. While they were young, all the cares of the children of both sexes rested on her shoulders. Later she was occupied much more with the girls, although the making and keeping clean of the boys’ clothing continued to be her responsibility. Daughters and daughters-in-law were used only as helpers in housekeeping by the mother, who always gave them specific tasks, while reserving for herself the general organizing of the work.

{61.} Housework was always subordinate to farm work. The job designated by the gazda had to be done first, and only if time allowed could other things follow. The gazdasszony was the go-between for the gazda and the members of the family. They told her all their wishes, and she, at the right time and in the right way, passed them on to the gazda.

The unmarried lads (legények) and married men formed the most important part of the large family’s work force. The oldest son, or in the case of an extended large family, the brother of the gazda as the next in line, had a certain sphere of authority in directing the work. But this was limited only to the organization of tasks designated by the gazda.

One of the most important duties of the young men or lads and the married men was to take care of the livestock. They were always the ones who worked with the oxen and horses and who supplied them with fodder, and they also milked the cows, which on the Great Plain especially was the men’s job. Harnessing and driving the animals, and the agricultural work performed with animals was always carried out by the young men and the married men, as was all the work done with the scythe. Threshing, the treading out of grain, and in general all the work that required greater physical power fell to their lot.

A special place was due among the men to the vő (son-in-law), that is, to the man who married the gazda’s daughter and moved in with her family. According to the conditions of property, the connection here could be of various kinds. If the young man lived in good material circumstances, similar to those of the bride, the marriage came about mostly to join properties. In this case the situation of the new husband equalled that of the gazda’s son, and he came to the girl’s house with a trousseau of clothes, just as brides did in other cases. The son-in-law who brought little or no property, and especially livestock, into the marriage had a more difficult status. He lived more or less at the level of a hired hand and could not let his voice be heard in any matter. His wife gave orders even in the smaller family, since he shared in the property through her. Sometimes the gazda’s daughter was married to the hired hand, either because she got pregnant and no other solution could be found, or because they judged him diligent, or perhaps because for some reason no one had asked to marry the girl (e.g. because of physical disability). Such a son-in-law was held in even lower esteem than a hired hand, although it often happened that after the death of the gazda and of his successor, the son-in-law himself became the gazda.

It could also happen that the son-in-law could no longer stand the humiliating situation and moved out. He could ask in such cases to be paid for the time he spent there at least as much as they would have paid a servant. It could also happen that the wife died, and if the gazda was satisfied with the son-in-law’s work, and could not do without it, then he tried everything to keep him there for the future. In such a case, the widowed son-in-law might marry a younger sister, or else, he could choose a wife from among the relatives. In rare instances he was even permitted to bring an outsider or widow to the house. However, if there was no possible solution, he was able to leave. At such times he also took his children away and for his work he generally got one and a half times as much as he could have earned as a hired hand. This was the main {62.} reason why the gazda tried to keep him on the family together with his children, who were the working force of the future.

The women of the family and the extended family are partly descendants of the gazda, partly the wives of his grown sons, the menyecskék (young wives). The daughters had more rights and the mother overlooked more of their doings than those of the daughters-in-law. This, however, did not mean that they did not have to participate in agricultural work in the fields. Among the chores of the daughters at home was to care for the garden, especially the flower garden in front of the house, and to take part in processing the hemp, but they rarely participated in housekeeping. A daughter’s most important task was to get married as soon as possible, in spite of the fact that folk wisdom held that “one girl is better off than a hundred young wives”. The daughters who were under direct supervision of the gazdasszony worked much less than the young wives and could take part in much more entertainment.

Basically the young wife who came from another family became a member of her husband’s family in every respect and assimilated into it entirely. In certain parts of the linguistic territory she called her husband’s elder brother nagyobbik uram (my older husband), and his younger brother kisebbik uram (my younger husband). If her husband died, some male member of the family often married her, because they did not readily let a good worker out of the family. The young wives also participated in all agricultural work. The extent of this changed through time. Thus only the women harvested with the sickle, while the men used only the scythe. In the latter case the women laid what had been cut in swaths. They could work around the house only if the gazda permitted it. At such times the gazdasszony indicated the necessary chores in the house and in the garden, or perhaps she sent them with milk, eggs, and chicken to the market. Generally the gazdasszony or the oldest of the wives cared for the children, for, compared to the others, she had greater authority and could order the young ones about. The wife had to help in the field work even when she was nursing, and at best she could go home at noon to feed her young one and on her return bring lunch back with her.

Divorce was a rare occurrence during the last century even in Protestant areas. In the case of divorce the wife moved back to her parents and took along her smaller children. Among the poorer folk, the older boy went with his mother, while the older daughter stayed with her father. Since the men were the breadwinners, and the girls and women took care of the house, the divided family was thus capable of living on.

The extended family, and often even the nuclear family, kept certain orphaned, or unmarried relatives. These took part in all the work according to their strength, but they did not have any rights and they were made to feel at all times that they were being kept out of charity. Although they could sit at the table, such men in most cases were assigned their sleeping quarters in the barn.

Boldog, Pest County

Peasant families that possessed property too large to cultivate themselves, kept some farm hands (cseléd), servants, and maidservants. To a certain degree these were looked upon as members of the family during {63.} the time of their service. The words család and cseléd (family–farm hand), of Slavic origin, indicates this phenomenon. The word has been split into these two senses from the 16th century on. The first part of it came to mean permanently “family” (család), the second “farm hand” (cseléd). Farm hands were hired for one year. The youngest often had not yet reached the age of ten and got nothing but food and perhaps some pieces of second-hand clothing. Their task was most often to guard animals and to do small jobs around the house. The grown farm hands did all the work around the animals and in the fields. They earned less working for the peasants of the village than on the large estates. Thus farm hands derived from the poorest layer of peasant society, so that to them even the meagerly dished-out food meant a great deal. Usually 6 to 8 quintals of grain, a pair of boots, and some little spending money made up the bulk of their salary. They could not get married, for the gazda insisted upon this condition during hiring. A maid servant (szolgáló) could only be found among more prosperous peasants when the {64.} gazdasszony needed help because of the size of the house or because of the state of her health.

Family life was regulated in every respect by strict patriarchal customs. This was also expressed in the order of the meals. The gazda, as the head of the family, sat at the head of the table. Alongside him sat his sons according to age, followed by the sons-in-law, and finally by the servants. The gazda reached into the dishes first, and consequently he took the best pieces. The rest of them followed in a pre-arranged order. In certain parts of the linguistic territory the women could not even start eating until the men had finished. Then they gave food to the children and also helped themselves to the left-overs. Usually they did not even sit at the table but ate their food off their knees, sitting on little stools or on the threshold. Breaking a loaf was mostly the job of the head of the family, who in Catholic areas first drew a cross with the point of the knife on the bottom of the bread. Thus the bread is a real symbol of the extended family, and while they lived on “the same bread” (egy kenyéren), that is to say, farmed together, this served as a common tie among them.

With regard to sleeping quarters the prevailing order changed from area to area but was the same in the same region. Thus in the Great Plain the gazda and his wife slept in one bed, in the front part of the room close to the window. The other one or two beds were used by the grown son and his wife, while the children slept together in box-like cots that could be pulled out from under the beds, or perhaps together with the old folk in the corner between the wall and the oven. The young men and the farm hands spent the night in the barn, because in this way they could take care of the animals better, and also it was harder to keep track of their staying out at night. In many places, the gazda slept from spring to autumn on the porch, where not only was the air more fresh but he could also keep an eye on the yard. In Palots areas the men slept in the front room called the első ház (first house), while the womenfolk found shelter in an unheated chamber or kamara with a tiny window. Here most of the space was taken up by beds, interspersed with chests containing the personal belongings of each girl or woman. Across the door stood the bed and chest of the gazdasszony, and around it, those of the rest according to rank. The children grew up in this chamber. They could be taken into a heated area only for bathing. Above each woman’s bed on a rod hung her dresses and her Sunday boots.

The patriarchal nature of family organization is demonstrated in the order of inheritance. During the last century, changing forms of inheritance developed according to region, depending in the first instance on the extent of state pressure to assure that female members of the family could inherit land when the property was divided as a consequence of the breaking up of the extended family. That is to say, we cannot speak of inheriting in the case of the extended family, since after the death of the old gazda his oldest son or perhaps his brother generally took over the entire property and the direction of the work along with it. After the death of a heavy-handed gazda, tensions and disruptive forces usually broke up the family, and then the questions that arose about inheritance were similar to those in the case of the nuclear family.

{65.} Generally, daughters did not inherit landed property among the Hungarian peasantry. When they were married off they got their under- and outer-garments, differing in quantity and quality according to regions. Formerly they got a dower-chest and later a bed, a chest, or some other kind of furniture. The prosperous sometimes also gave a cow or calf, so that the young wife could cover her expenses out of its profit. Sometimes they gave the young wife a piece of the hemp fields outside the village. Since the second half of the last century, daughters have also received their share from the property, but usually they got compensation only in the form of money. The inheriting of land by daughters on an equal basis with sons began to spread only in this century, but it never became customary.

The sons did not in every instance receive an equal share. The oldest son, if he left the family because of his marriage, usually got from the land and perhaps from the stock the share due to him. This was generally smaller than what he would have received from an equal distribution, because they clearly did not want to impair the productivity of the remaining land. The youngest son stayed with the parents longest by the law of nature, and accordingly he inherited the house and its furnishing, and the land that was left after satisfying his brothers and sisters, along with the agricultural equipment. For this he nursed the old folk in their afflictions, and took care of their burial. In such cases the older siblings received only some souvenirs from the furnishing of the house. The right of the youngest son to the house of his parents was not only recognized by Hungarian lawbooks from the 16th century, but was also made mandatory, and certain records from the beginning of the 12th to 13th centuries already mention this. The peculiar situation of the youngest son is widely reflected in the folk tales and other creations of folk poetry. The father could disinherit his son from the property, but this happened very rarely. Beginning with the 19th century it happened more often that a talented child was further educated by his parents to be a teacher or priest or, more rarely, to pursue some other profession. In this case he either did not receive a share from the inheritance or got a reduced share on the assumption that his rights were already satisfied by the sum spent on his education.

Hungarian Plain. End of the 19th century

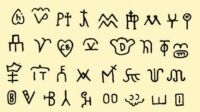

The tangible property belonging to the family was identified by an ownership mark, so that it was easily recognizable and ownership proven with its help (cf p. 259). The most commonly known is the animal mark or brand, used primarily on horses and cattle. This was inherited within the family through several generations and usually contained the initials of the gazda. If there was more than one similar brand within a village, they were differentiated by an X or star or some other sign. It could also happen, in the interest of more specific {66.} distinction, that they used the mark of the settlement along with the family mark if they wanted to drive the stock a distance. Everybody knew the mark of a certain family in the village, and so they burned it on agricultural implements as well. We even know instances when they marked the gravepost with it, indicating the family to which the deceased had belonged. In vine-growing regions they used the branding iron to mark the barrels (cf. p. 408.

Kecskemét. 19th century

Sheep and pigs were marked by trimming and notching their ears in a certain way which passed through generations within one family, but in some places the notching of the sheep’s ear indicated its age. Compared to the above, the marking of the small stock was less regular. Marks were cut into the web on the feet of geese and ducks, while a chick’s toenail was removed. If they wandered off, they could be easily identified with these aids. The women sewed marks into their clothes and underwear, so that they should not get mixed up during washing. However, these marks designated not the family, but rather the individual members within it.

| On the History of Family Organization | CONTENTS | The Troop, Clan, Kindred |