| The Rural Agricultural Labourers | CONTENTS | Seasonal Workers |

Share Labourers

For centuries the landless farm labourers performed agricultural work primarily for a certain portion of the yield. This labour method really expanded after the freeing of the serfs, when the large estates that did not possess capital suddenly lost the free labour of the serfs. There was no other choice but to hire share labourers to harvest, to cultivate and harvest corn, and to cultivate various industrial crops. There came from all this such a jumble of connections that it hindered the labourer’s free movement and tended to tie him more closely to one place.

Share harvesters in the 18th century still received a sixth or seventh portion of the crop for their work (cf. pp. 504–7). By the turn of the 19th to 20th centuries this share decreased to a tenth or eleventh portion and both the cutter and binder of the sheaves received this amount together. From the beginning of the last century these conditions were fixed in writing on the large estates. The harvesting gazda had usually concluded these harvesting contracts in February with the steward of the estate in the name of the harvesters. They agreed upon the ratio of the share and, furthermore, upon how the work was to be done and how much time they would need to do it. If somebody fell sick, they let him go and at most paid him for the work already finished. The gazda supplied drinking water, but the labourers had to pour it into jugs and carry it around. If a storm scattered the sheaves they had to gather them together as often as was necessary.

Several methods of having meals developed. The large estates generally doled out weekly a so-called payment in kind consisting of bread, bacon, flour, vegetables, perhaps lard, vinegar, and always brandy, or in some areas wine, of varying quantity, out of which the woman who cooked for the harvesters prepared the midday dinner and sometimes the supper. At other places the estate customarily took charge of the cooking, but because this gave ample opportunity to cheat, the labourers preferred payment in kind. The providing of cooked meals survived for a long time in the case of the rich and middle peasants, where the food of the one or two harvesting couples was the same as that of the gazda.

Harvesting usually lasted from two to four weeks, and since the harvesters started early, normally before dawn, they went home only if they worked in the vicinity of the village. In most cases they slept outside, or perhaps sought shelter at the nearest farmstead. On the large estates they emptied one of the barns at such times and the share harvesters slept there on straw.

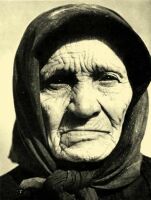

Öszöd, Somogy County

They made contracts in various ways. There were those who hired {80.} themselves out only for the harvest itself, which was over with the stocking of the sheaves. Others also assumed responsibility for carting in the crop, loading the cart and lifting the shocks. There were some who also saw to the treading out and threshing, and later the work of machine-threshing, which gave them a certain extra income.

They had to complete harvesting in a definite time or else the seed dropped from the ear, which meant a great loss to the gazda. The harvesting labourers, in order to increase their share, went on strike immediately before harvest or during it to assert their rights. At such times the gendarmes beat down their efforts. They carried off the organizers and put them in jail, while the intimidated remainder started to work again. The landowners feared harvesting strikes from the end of the last century on, and as a consequence they tried to tie down the workers in various ways. One method of this was the cultivation of share maize.

Generally, this work was given only to those who took on harvesting. {81.} Depending on circumstances, it amounted to one or two hectares. This was ploughed, seeded, and handed over by the estate to the share labourer, who hoed it three times, harvested it, and cut and stacked it. For this work earlier he got half the crop, later on one third, then one fourth of it. But if he participated in the harvester strike his cornfield was taken away from him, which meant that the following winter he was unable to fatten a pig.

From the turn of the century, various industrial crops, especially sugar beet, gained significance on the large estates. They tried to devise the cheapest possible means of paying for labour on them. Therefore they made a contract with the share harvesters and share labourers of corn that required them to do any kind of work for the customary daily wage all through the year, whenever the estate was in need of them. This meant that the share labourer could not go anywhere, for example to take on a more profitable job, because the estate, if the labourer did not show up immediately, broke the contract and he lost the foundation of his livelihood.

Great Plain

This contract stipulated not only the above conditions, but also that the share labourer was obliged to do without pay for a few days any kind of work designated by the employer. During this time he got neither a daily payment or wage, nor food. In the previous ways of organization, but especially in this so-called “working-off” system, the direct continuation of feudal serf services can easily be recognized. The share {82.} harvesters usually were obliged to provide services during one or two days, mostly carting in the unthreshed grain without being paid for it. The labour on the fields of maize meant an even higher rate of unpaid work. In the Great Plain it varied between one and three days per cadastral acre (1.42 acres), but in certain counties of Transdanubia it even reached as much as seven days.

After threshing, the harvesters carried their share home on a cart hired communally and paid for the cost proportionately. In some places they succeeded in charging it to the estate. In the evening or even during the noon break, the harvesters often sang, and songs about harvesting occur often. They liked to listen to tales, myths, true stories, soldiering experiences, and the one who knew a lot of these gained great respect.

The share harvesters, under the leadership of certain gazdas, worked together sometimes for decades, and hung together not only in work, but in everyday life, in the village and in entertainments as well.

| The Rural Agricultural Labourers | CONTENTS | Seasonal Workers |