| Layout, Fireplace and Lighting | CONTENTS | Outbuildings of the Farmyard |

Furniture Arrangement in the Dwelling Houses

The form of furniture, especially its decoration, changed relatively rapidly in response to the prevailing fashion of the time and the historical development of ornamental folk art. However, permanent rules prevailed in the manner of furnishing the buildings, rules determined by such factors as the character of the work done there, life style, and, last but not least, tradition. Therefore, change in this respect was much more slow, and the new elements were fitted into the former system.

Several historical periods may be differentiated in furnishing the room of a peasant house. In the earlier period banks of clay were built against the walls all around, and were used for sitting, sleeping, and keeping certain articles of clothing. The clay banks were replaced by wooden benches, standing on posts hammered into the ground and having no backs. Among the Palotses a general use of clay and wooden banks still existed in the last century, but in our century they can be found only among the Csángós. The place of the hearth, even in this period, was in the interior wall of the room, and close to those still in use a few decades ago among herdsmen and farmstead dwellers of the Great Plain. A round opening could be cut in the centre of the table so that the cauldron could be placed into it and the family would eat out of the cauldron communally. Nails were hammered into the wall to hang up footwear and articles of clothing, and maybe sometimes little shelves were fixed up for containing smaller objects. Clothes were also hung on rods fastened from beams.

Sióagárd, Tolna County

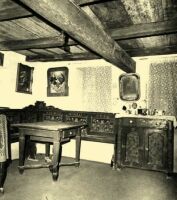

At the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of modern times began the gradual separation of work and living space within the peasant room, as a result of which, besides the banks, new pieces of furniture began to appear: the table, the chest, the bed, and the chair. The table gained a special significance among these and was placed in the corner opposite the fireplace. Its original form probably was a board standing {158.} on four legs hammered into the ground, later replaced by drawered (fiókos) tables and tables with a “pantry” below them (kamarás asztal). These carried the signs of various stylistic trends. The table was surrounded by two benches standing against the corner, on which the place of honour belonged to the head of the house and, next to him, to the eldest son. The housewife could get a place only at the fireplace side, but in a significant part of the Hungarian linguistic territory women and girls were not allowed to sit down to the table, but ate their food sitting on small chairs or on the threshold after the men had finished.

Hollókő, Nógrád County

Decs, Tolna County

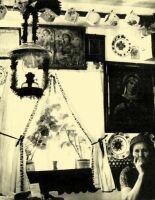

As the table gained acceptance, the room was divided into two sections. The place of work developed around the fireplace, where they cooked and, according to need, did work on a bigger or smaller scale such as woodcarving, repairing of smaller tools, washing, etc. We can rightly call the table and its vicinity the sacred corner (szent sarok); they inserted the “foundation sacrifice” (építőáldozat) into this part of the house. From bones found under this corner of the building we know that roosters were used as foundation sacrifices from around the 11th up to the 13th centuries. The burying of horse and dog skulls also occurred, and in one of the great Hungarian ballads of medieval origin the forever crumbling walls of the fortress Déva were fortified by walling in the ashes of the wife of Stonemason Kelemen (cf. pp. 524–527). In Catholic areas pictures of holy images, the bridal wreath, and perhaps a cross and a household altar, as well as statues brought back from pilgrimages, are placed in the inner corner of the house. In {160.} Protestant areas, prints depicting national heroes, the picture of the master of the house as a soldier, the Bible on a small wall shelf, a book of psalms, penny novels, calendars, notes and official documents are put here. The prettiest plates are also hung on these walls in pairs.

The beds are placed parallel to each other on two sides of the wall. Among these the one standing in the corner opposite the table is the highest ranking. This is used by the man of the house and his wife. The other bed in the opposite corner, behind the door, is the sleeping place of the newlyweds. Between the bed of the newlyweds and the hearth is a small and simple bed-like plank structure standing on four legs, on which the children sleep.

Mezőkövesd

Parád, Heves County

At each end of the two benches surrounding the table, place is provided for a chest for keeping clothes. The chests were replaced in the second half of the last century by a three- or four-drawered chest of drawers (komót, sublót). Above the chest is a slightly forward tilted mirror, and behind that there is a place well suited for putting away {161.} books, newspapers and documents. They put memorabilia on top of the commode, such as presents from the fair: ginger bread, coloured pots, small statues, glasses, a cross, a piggy bank, etc.

In this form of furnishing, benches were not used much, so that they lost their multiple function. At first they were put around the table, but it could happen that one was placed in front of the bed. In many places they preferred to put chairs there, usually two, in rare cases three, because these could be pulled up to the empty sides of the table at mealtimes. This furnishing was at most completed by a flat cupboard (falitéka) or corner cupboard (saroktéka), in which they kept books, medicine, brandy, and in general such things as it was desirable to keep under lock and key.

If there were two rooms in the house, to the left and right of the kitchen, then these were furnished similarly with more or less identical furniture. The difference was only that they put the better, newer, more ornamental furniture in the “clean” or “best” room (tiszta szoba), used rarely, and only for guests.

Mátisfalva, former Udvarhely County

The corner arrangement that could be called typical throughout the entire Hungarian linguistic territory began to break up during the second half of the last century. Until then there were two windows in {162.} the room, close to the table that stood in the corner, one window on the street side, and one on the yard side. As a consequence it was possible to ascertain even from the outside where the sacred corner stood. The next phase was two windows looking out symmetrically onto the street side, and in this case the table was placed between these windows across from the door. Behind it, instead of the two benches, only one chest-seat was placed, in which clothes were stored, but if necessary it could also serve for sleeping. A mirror, plates and pictures were hung above it. Some were hung over the beds, which stood parallel to each other against the walls, so that in such an arrangement the sacred corner essentially ceased to exist, or at any rate some of its elements moved to the two sides.

In this parallel form of arrangement they placed two chests at the foot of the beds left and right of the table, or placed a piece of furniture there which followed the chest in time sequence and served to store clothes such as a wardrobe, or a sideboard. In most parts of the linguistic region this method of arranging furniture eclipsed the corner arrangement in less than half a century.

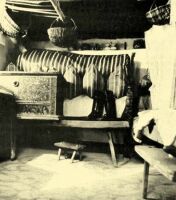

We can scarcely speak of the traditional arrangement of the kitchen, since until the most recent times there was very little furniture in the Hungarian kitchen. The kitchen, consequently, preserved its archaic character better than the living room. Here structures shaped from clay and used for baking and cooking remained longer. Most kitchen utensils were hung on the wall in a prescribed order. The reason why the kitchen interior developed more slowly rests in the fact that usually smoke was channelled from the room through the kitchen, above which a chimney was raised. Thus the kitchen generally did not keep up with the development of the rest of the building, as vaulting, which meant the complete removal of smoke, developed only much later.

Only in the front part of the kitchen, in the so-called pitvar, porch, the {163.} door of which opened onto the yard, was it possible to put furniture. An example is the low bench on which water containers stood. Another more furniture-like piece is the sideboard (tálas) for storing kitchen dishes; the top part was for putting plates behind a rail; larger cooking pots were kept in the broader lower section of the sideboard. (On furniture, cf also pp. 381–89.)

| Layout, Fireplace and Lighting | CONTENTS | Outbuildings of the Farmyard |