| Acquiring Raw Material from Flora and Fauna | CONTENTS | Farming |

Food Gathering

Great Plain

By the time of the Hungarian Middle Ages, food gathering did not play a significant role in relation to productive activity, but it doubtless did at an earlier time in supplementing food. Man simply took from nature all he could use but did not pay attention to replenishing or preserving it. Gleaning, therefore, can be carried out successfully only over very large {193.} areas. Consequently, it follows that as the population increased in numbers and as the country became more and more a cultivated region, the amount of food gathering decreased continually. However, it has not completely disappeared even today, since the collecting of mushrooms, herbs, and certain fruits (raspberry, wild strawberry) still survives.

The nature of the soil and climate determines the nature of wild-growing plants, and the natural plant cover determines the method and tools of food gathering. For this reason, food gathering is different in the world of the swamps, or on the steppes of the Great Plain, from food gathering in the mountain forests.

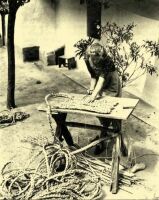

Tisza region, 1920s

Up until the middle–but in many places until the end–of the last century the central part of the country was covered by a permanent swamp region, which was renewed every year by the flooding of the rivers. This offered many kinds of food and numerous raw materials. The water chestnut (Trapa natans), flourished in the quieter still waters. It was harvested in the early autumn days from a boat. Its prickly fruit got caught on a piece of ragged felt or a sheep’s tail they pulled through the water. In other places water chestnuts were found in such quantities that they raked them out of the water, or fished them out with a piece of fur through a hole cut in the ice. People boiled them and ate the white, {194.} crumbling, chestnut-like interior, or they kneaded it into dough or, by mixing it with flour, even made bread of it. A favourite food of the people of the Great Plain was the millet-like glyceria (harmatkása). They held a sieve under it early in the morning and shook the seeds out. They ate it mixed with eggs as griddle cakes. Herdsmen baked the floury stem of the bulrush (Typha L.) in a fire. Biscuits were also made out of it. The sources refer to it mostly as famine food.

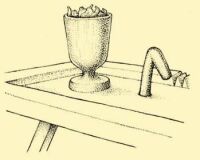

Debrecen. Early 20th century.

a) A cup for measuring water chestnuts. b) A hook used when cutting off the thorns from the cooked water chestnuts

A great treasure of swampy regions is reed (Phragmites), which was harvested in the winter after the water had frozen. It was cut with a long-handled scythe, the so-called toló, made with a stout blade, to each end of which a long pole was fastened and it was pushed through the reeds. When enough reeds gathered in the centre, they lifted them out and tied them in sheaves, then piled these in conical heaps at the edge of the swamp or on one of its islands. Reeds were used not only for roofing the house, but were also made into fences and windbreaks for the stock. Reeds were put under the child in the crib and also into the grave, against groundwater. Thus reeds accompanied men living in the swamps from the cradle to the grave.

The gathering of the bulrush (Typha L.) took place in August either from a boat or by wading in the water, in which case a serious battle had to be fought with the leeches that proliferated. The bulrushes were taken home (cf. Ill. 151) after having been dried on the shore, to make baskets, bags, beehives (cf. Ill. 116), and covers out of. Some villages outstanding for bulrush mat-making survived for a long time, and shipped their products to faraway markets.

A characteristic food-gathering figure of the Great Plain swamps was the pákász. He spent his entire life in the marshes, among the reeds, his hut standing on a salient part of one of the islands. He rarely had a family and went into the village only if he wanted to exchange some fish, game, or feathers for food. He collected water chestnuts, gathered the glyceria and the bulrush, fished and caught birds with his hands or with tools. He sought out the nests of the waterfowl and took their eggs and their already edible young by the thousand. He acquired the most beautiful feathers for the hats of the village lads, who always gave him food or good money for them. This man of a peculiar life style disappeared at the end of the last century, when the swamps were dried.

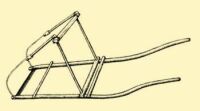

Gárdony, Fejér County. Around 1950

Medicinal herbs constitute an important product of food gathering. As a Hungarian proverb has it, “There is medicine in weeds and trees”. Actually, folk medicine used plants in many very versatile ways, some of which are still employed today. Such are, among others, the camomile (Matricaria R.) which was picked with a comb-like tool, and the fruit of the cranberry (Vaccinium L.). In the winter, medicinal tea is brewed from the flowers of the linden tree (Tilia L.). They dried the various roots and stored them thus for the winter, for the time of sickness. The folk use of medicinal herbs is often in agreement with the advice of medieval books on medicine, which slowly filtered down and became part of folk knowledge.

The true home of food gathering is the mountain region, the forest. At one time even the trees were felled in such a way that no one thought of their replacement. They cut the huge timbers in the winter. Some {195.} they chopped up on the spot and took home that way, others were marked with a proprietary sign in order to avoid losing them and slid them down to the valley whole. From here they were carried to the river, where everybody looked for his own as indicated by the mark that had been put on after felling. Huge rafts were made from the timber and floated in this way down to the Great Plain.

Many things were made out of the wood. Charcoal was burned, some on the spot, or potash, indispensable for glass making, was prepared. Axle grease was also made from wood. Some cut notches into pine trees and allowed the resin that came out of the wounds to drip into vessels made from bark. When the sap begins to circulate in the trees during spring, they tap them. The birch is especially suited for this. The nyírvíz or, as the Székely call it, virics, is a sweetish liquid, which was used fermented in the past. It was sold far and wide at the Great Plain fairs of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Kiskunfélegyháza

The forest region is extremely rich in mushrooms. In many places {196.} people are familiar with it and regularly gather 30 to 40 edible varieties. The forest not only provides heating fuel, but the fallen leaves when gathered are an excellent bedding for the stock and, in times of great need, are mixed with other fodder to serve as famine food until grass sprouts in the spring. In many places they even cut the bark off the trees and collect the fruits of the forest in vessels made out of it. In times of famine, people used the cut off, dried, and ground-up bark of the beech tree and acorns, from which, mixed with flour, they made bread.

There are many ways to make use of the fruits of the trees. Thus, wild fruit (apple, pear) is dried and in some places vinegar or refreshing drinks are made out of them. Jam was made from the fruit of the dog-rose bush, from raspberry and wild strawberry.

The economic significance of food gathering is not great, but its unusually large variety implies in most cases a long historical past. During the past two centuries, its significance grew especially at times when the plough lands were ruined by the ravages of war or when a long-lasting drought devastated the crop.

| Acquiring Raw Material from Flora and Fauna | CONTENTS | Farming |