| The System of Hungarian Farming | CONTENTS | Sowing |

Soil Cultivation

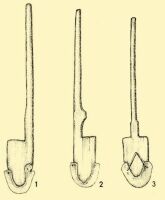

Among the hand tools for cultivating the soil, one of the most important is the spade. The wooden spade was fitted with an iron shoe, which not only made the work easier but also prevented wear. It seems that the symmetrical forms with the two-sided blade with a double step are known in the central and western half of the linguistic region, while the {198.} asymmetrical, one-sided blade is known in the eastern region. Historical sources mention spades with blades completely of iron from the 16th century. These were shipped from small foundries to distant lands. They have similar forms all over the country, and only perhaps in the placing and size of the blade top are there smaller differences.

1–2. Magyarvalkó, former Kolozs County. 3. Székelyland

Early 20th century

The hoe is much more varied. Some of half-moon shape are linked to the Balkans. The square ones seem to come from the west. Great variety is shown among the pointed hoes, the characteristic forms of which are designated by the name of the place or region where they are primarily used. We can estimate the number of the types of the various hoes to be at least one hundred, all of which were well known by the small foundries and hoe factories that sent the appropriate form to merchants everywhere. In the mountain region a shorter handle, and in flat areas a longer handle was fitted to the differently shaped hoes in order to accommodate them to working conditions.

Magyarvalkó, former Kolozs County. Late 19th century

Szimó, former Komárom County. Late 19th century

In recent times, there is more and more evidence that the pre-Conquest Magyars knew and practised plough farming in the 7th to 9th centuries. First of all, the Hungarian vocabulary testifies to this. The word eke (plough) itself is Bulgaro-Turkic in origin; the word köldök, the term for the piece of wood which connects the plough beam with the mouldboard of the plough, is from the same source. If we add to this that the terminology of the plough has many words of Finno-Ugric origin (talp, mouldboard; ekefő, share beam; szántóvas, plough share; laposvas, flat iron; hosszúvas, long iron; vezér, head; szarv, handle), then we have before us a furrow-turning plough capable of cultivating the cropland. Archeological evidence also proves that the true Magyars could have become acquainted with such a plough either in the Bulgarian Khaganate or in the Khazar Khaganate. Such a large quantity of plough irons has turned up from the excavations there as to prove the wide use of the plough.

Kökényespuszta, Nógrád County

On the great South Russian steppes the Magyars also met various Eastern Slavic peoples who possessed a highly developed plough culture. {199.} Some further terms prove that the ploughs of these peoples could have been more developed than the ones earlier known to the Magyars (gerendely, plough beam; taliga, forecarriage; ösztöke, goad; etc.). In recent years Soviet archeologists have excavated in the Ukraine numerous asymmetrical plough shares dating from the 9th and 10th centuries, which proves that these Slavic tribes had already known and used the plough with a forecarriage that could be turned to one side and that improved considerably the quality of the cultivation of the soil. The plough thus arrived at a degree of development which cannot be surpassed even today, as only the pulling power has increased since then.

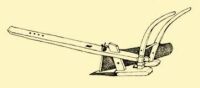

(Debrecen type plough). Kunmadaras, Szolnok County. Second half of 19th century

We must mention that among the finds in Hungary, asymmetrical plough shares and coulters appeared only in the 12th–13th centuries. This may be because the value of iron was so great at this time that iron objects survived only when the settlement was destroyed so suddenly that it was not possible to save them. In other cases, people used even completely worn iron objects for the most varied purposes. Perhaps this may be the reason why no asymmetrical plough irons and coulters have turned up so far from the 10th and 11th centuries.

Berzence, Somogy County. Early 20th century

In the 19th century, the peasants themselves made the frame of the plough in areas rich in wood. However, there were many villages in the mountain regions of the Carpathian Basin, where the population was occupied with plough making. They hauled their merchandise, adjusted to local demands, to the fairs of the Great Plain in the spring and exchanged them for grain or sold them for money. In certain villages and towns plough makers operated, but in most places the frames of the ploughs were shaped by the cartwrights and wheelwrights.

{200.} The wooden plough had only two iron parts: the plough share and the coulter. Earlier these were made by the village blacksmith. Beginning with the 17th century, town and country assessments set their prices exactly. Later on the foundries produced a significant part of them, and the task of the blacksmith was limited to their furnishing and shaping. In most settlements the first obligation of the village blacksmith was to see to sharpening the plough share and the coulter in return for the wages paid him by the farmers.

It is not a difficult task to describe the Magyar wooden ploughs. They form two large groups, symmetrical or asymmetrical. All of the mouldboard ploughs and the majority of their frames are rectangular. Their plough beam is mostly straight so that only in such smaller, isolated areas as the southern part of the linguistic region do we find ploughs with a curved beam. Within the larger units, the ploughs of Hungary can be divided into smaller groups on the basis of the relation between and the location of the handle and the mouldboard.

Symmetrical ploughs are symmetrical in every respect, including the plough share. Such were the furrow-turning ploughs, on either side of which was fastened a mouldboard. Thus the ground was turned equally to the left and to the right. This form proliferated generally in the Middle Ages, but it was used only in peripheral areas by the 19th century. The reversible plough, which was completely symmetrical and had a single handle, most likely developed from this. The symmetry is broken only by the mouldboard, which can be switched from one side to the other, and along with it the coulter as well. This plough, by following the same path on the return, is especially well suited to ploughing hillsides. This form of the plough was widely used in Transylvania and was known as well in Slovakia and in certain regions of Gömör. Most recent studies have concluded that it most likely developed in the Carpathian Basin in several places independently from each other during the 16th and 17th centuries.

One of the most characteristic forms of the asymmetrical plough is the one on which the handle and mouldboard are carved out of a single piece of wood. This made the structure extremely sturdy. It was consequently especially well suited for breaking up hard, grassy soils. They ploughed with this during the past century in the northern and southern part of the Tiszántúl, in the Palots region and the areas south of them, between the Danube and the Tisza, and in the larger, eastern half of Transdanubia as well. We can therefore say that they used this form over the greater part of the Magyar linguistic territory.

If we search in the west for traces of this stilt-sole type of plough, it cannot be found, or only very rarely, and even then it can be proved to be borrowed in some way from the Hungarians. However, if we look for its proliferation toward the east, we find that is was used in Moldavia and in the Ukraine as well as in the great Russian steppes all the way to the Volga, and in some places was introduced by Russian settlers even to Siberia. Written and pictorial descriptions note the occurrence of these ploughs in the Ukraine and in Russia by at least the 15th century; furthermore, we know of data regarding the use of this type at the same time in Hungary as well. Thus, on the basis of linguistic, archaeological, {201.} historical, and ethnographical data, it is very likely that the Magyars became acquainted with this kind of plough in the 9th century. Because it was suited to the soil conditions in the Carpathian Basin, the type continued to be used here right up to the 19th century, when the half iron and iron ploughs completely replaced it.

In the central part of the Tiszántúl, that is, in the region east of the Tisza, in Transylvania, and in the western part of Transdanubia as well, wooden ploughs were used, the two handles of which were joined onto a separate, flat mouldboard. This heavy tool was dragged by six to eight oxen, in order to turn the soil 10 to 15 cm deep. This plough supposedly developed from the most simple type of rooting plough.

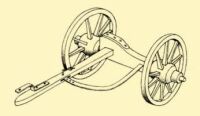

In the Carpathian Basin, almost every plough has a forecarriage. This assures the balanced movement of the plough, and with its help the depth and width of the ploughing can be controlled. The fairly uniform kinds can be divided into two broad groups.

The two wheels of the symmetrical forecarriage of a plough are identical, the beam being located in the centre. There is no way to control the forecarriages on the furrow-turning plough. The width of the furrow can be determined on the forecarriages of the reversible plough by a wood or iron arch shaped in a half circle, the cságató. The depth is determined in both cases by the degree to which they push the forecarriage under the plough beam.

The wheels of the forecarriage of the asymmetrical plough are different in size. The larger moves along in the furrow, the smaller one on the unploughed ground. The beam of the forecarriage is pushed to the right and above it the plough beam is connected to the bolster. The cságató determines the width of the ploughing; it starts out from the left side of the axle and is attached to the beam of the forecarriage by means of holes set at the desired distance. Such a forecarriage of the mouldboard is generally known in the entire Carpathian Basin, where it can be found more frequently to the east and less so towards the west.

The half iron ploughs, at first made in western countries and later imitated at home, appeared in Hungary during the first half of the last century. The first factory, the Vidacs Plough Factory, opened in the 1840s. The number of such ploughs in use in the country in 1848 can be estimated at 2 to 3 per cent, and even ten years later the number did not reach 10 per cent. In 1871, in the large grain producing areas (Great Plain, Little Plain), their numbers already surpassed 90 per cent, yet remained mostly at under 10 per cent in the peripheral regions. However, by 1920, except in some areas of the Carpathian Basin where ancient modes continued to prevail, wooden ploughs largely had disappeared and had been replaced by the all-iron plough.

One important adjunct of the mouldboard plough is the goad pattle (ösztöke). This consists of a small iron blade and a short wooden handle. They cleaned the mud from the plough share with it and picked out the weeds that got stuck in its crevices. It was held in the hand, because it could be used to urge on a lazy beast, or else was fixed by the handle and only taken out when there appeared to be a need for it.

The plough was hauled to the field in a cart or by a plough slip (ekecsúsztató), of which the most simple form is a V-shaped piece of {202.} wood. The plough is rolled onto it in such way that its handle slides on the ground while the plough beam is fastened to the forecarriage of the plough, and in this fashion it is dragged to the desired spot. Its advantage is that by carrying the plough on the slipe they spared the animals. Its disadvantage is that it wrecked the road, so that the authorities strongly forbade its use. As a result, wheeled versions developed later on, some of which grew practically into small carts.

In the Carpathian Basin, during the Middle Ages and even in later times, cattle, primarily oxen, pulled the plough. They harnessed six to eight oxen to larger ploughs on more difficult soil, and two to four oxen to smaller ploughs. In such cases one man drove, that is, directed the oxen, while the other held the plough handle. Oxen were more and more replaced by horses from the 18th century on, especially in the Tiszántúl, where they preferred the faster moving horses for getting around between the farmsteads. We find in many places, especially in the 19th and 20th centuries, that cows were put to the yoke in ploughing, but always at the hands of the poorest peasants. The bison as a plough animal occurs first of all in Transylvania and in smaller numbers in the southern part of Transdanubia.

The first spring ploughing is the great event of peasant life. Usually they would not start on Friday, which was thought to be a day of ill omen, but on the lucky days of Tuesday and Thursday. When they first went out into the fields they sprinkled the cart, and even the man sitting on it, with water, so that he would be lucky all year round. They pulled the plough, which was laid onto the slipe, through some bread and an egg placed at the gate (Krasznokvajda, Abaúj County). If the egg remained whole they took it along and ploughed it into the first furrow, to assure a plentiful harvest.

Nyíri, Abaúj County. 1950s

The reversible plough always returned alongside the same track, ploughing in the opposite direction and as a consequence the mouldboard and coulter were reversed at the end of the field. The mouldboard plough could turn the soil only to one side, so that they had to take a wide turn with it, which is why they also called it detour plough. At the time of joint ploughing, they marked the centre of the field precisely and drew a furrow on it. They turned the next furrow immediately next to and toward the first one so that it created a ridge in the middle. They started the ploughing apart at the right corner of the field, so that the plough turned the soil toward the edge of the field. It was not necessary to mark the centre at this time, because the two last furrows marked it anyway at the end.

They ended up, after finishing the first furrow, on the opposite side of the field from where they began, turning the soil outward, and always turning to the left. Thus, at completion, a wide, deep furrow was formed in the middle of the field. They interchanged the two ploughing methods annually or often at each ploughing.

They used ridge and furrow ploughing (bakhátas szántás) on soil that was wet and hard to dry out. They divided the field into small strips 2 to 3 metres wide, and ploughed each of them by the joint ploughing system. Thus a ridge formed in the centre, from which the water drained easily into the furrows between. They used this ploughing method {203.} chiefly in western Hungary, but it also occurred in some of the swampy regions of the Great Plain.

Historical data show that, in connection with rotation farming, the practice of annually ploughing three times for the autumn grain had already developed generally by the end of the Middle Ages. The plough was entered most deeply at the last ploughing, which was then followed by sowing. For a long time they turned the soil only once in the spring for the spring grain. In the Great Plain, but especially in the Tiszántúl after the Turkish occupation, they ploughed for the autumn grain only once, rarely twice, and this practice survived even into the 20th century.

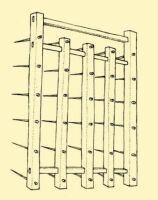

As the ploughed soil is usually lumpy, the toothed harrow is used to break it up. Its rectangular forms appear to be the older, its triangular forms the newer. They used the spike harrow generally in the central part of the Carpathian Basin, while at other places they used it sporadically, primarily to cover over the seeds.

| The System of Hungarian Farming | CONTENTS | Sowing |