| Transdanubia | CONTENTS | Great Plain |

Upper Hungary

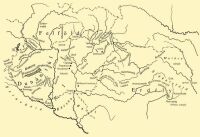

The largest ethnic group of Upper Hungary (the Felföld) is the Palots. Their name means Cumanian in Various Slavic languages, which might refer to their origin, but it is more likely that only their neighbours thought them to be Cumanian. Today, the traces of their relationship to the Cumans, which lives in tradition, cannot be easily discovered. Their settlements extend from the course of the Garam all the way to the centre of Borsod County, and in some places, even further. All the people in the north up to the Hungarian linguistic border are Palotses. Their boundaries are even more difficult to define on the south, because after the expulsion of the Turks, the prolific population emigrated even into the Southern Great Plain.

Precisely because the Palotses are dispersed over such an extremely large territory, we can differentiate several sub-groups among them. In general we speak of Western and Eastern Palotses. Among the former, the Palotses of Hont and Nógrád counties differ from each other. Several villages of the Medvesalja are just as isolated from the other villages as the settlements of Galgamente, whose rich embroidery, folk costumes, songs and dances are known far and wide. The smaller and larger groups of the Eastern Palotses are tied to certain geographic units. There is Erdőhát, south of the Sajó and Rima rivers. Its people, the Barkó, are so much like the Palotses that according to some they are part of this group. The Hegyhát is the hilly area enclosed by the streams Sajó, Bán and Hangony, while the Homok indicates a part of the valley of the stream called Tarna.

In spite of the differences among the various groups of the Palotses, the common features that unite them are still very numerous. The peculiarity of their dialect, which extends to several large areas, is taken {42.} as a basic determinative mark by many. The organization of the joint family prevailed with them for a long time. Shepherding played an especially important part in their animal husbandry, which is quite uniform, and its connections point toward Transylvania and Slovakia. They are also bound by many characteristics in house construction, homespuns, costumes, and folk poetry. We can point to Slovakian influence on the northern stretch of this group, especially in customs and beliefs, such as, e.g. kiszehajtás (throwing a straw dummy into the brook on Palm Sunday to avert the plague).

The Cserehát contains the villages between the Bódva and Hernád rivers. On the southern and eastern slopes of the Zemplén Mountains are the villages and market towns of Tokaj-Hegyalja. Life here in the past as well as in the present is determined by its far-famed vine growing. Because of the wine trade Greek, Serbian, Russian, Polish, Slovakian and German merchants lived here, a fact which can be felt in the culture, especially in connection with grapes, wine, and certain small crafts. To the north lie the 15 villages of Hegyköz. The difficult living circumstances of the people here are characterized by forestry work, animal husbandry and fruit growing.

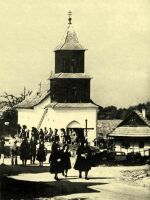

Hollókő, Nógrád County

On the border between Upper Hungary and the Great Plain, but already on the plains, live the Matyós in one larger and one smaller village (Mezőkövesd, Szentistván). Their Roman Catholic religion played a major role in their culture. Their name, as they proudly proclaim, is {43.} a diminutive form of the name of the great Hungarian king of the 15th century, Matthias. They were peasants and husbandmen, but most of their land was occupied by great estates, so that from the second half of the last century they were compelled to sign up as seasonal labourers (for 4–6 months) and thus earn a living in various parts of the country. The common, so-called hadas settlements of joint families and their organization (had–troop) can be well demonstrated until the most recent times. They have developed an extraordinarily colourful, rich embroidery and folk costume since the second half of the last century. Their material culture points toward the Great Plain, whilst their folklore seem closer to that of the Palotses.

| Transdanubia | CONTENTS | Great Plain |