| Seasonal Workers | CONTENTS | Agricultural Hands on Large Estates |

Pick and Shovel Men

The large-scale regulating of rivers and the construction of railroads, which required a great deal of earth moving, started in the second half of the last century. This was accomplished by the pick and shovel men (kubikos) from the southern half of the Great Plain, who were landless or possessed land only in rare cases (cf. p. 507). They were paid according to the vat (containing 25 gallons) of earth they lifted out, and the payment, unlike that of the farm labourers described above, generally was made in money.

The pick and shovel men also worked in bands, led by the gazda, and it was among his duties to organize the group. Therefore, when he heard from the newspaper or by word of mouth of some larger undertaking, he travelled there on his own or at shared expense to look over the {85.} situation and the opportunities to make money. If he found everything satisfactory, then he began to gather the band in such a way that he first assured a place for his good men and his relatives, among whom he picked out the foremen and their substitutes.

Region of Szentes, Csongrád County. First half of 20th century

The bandagazda of the pick and shovel men worked along with the others, but at the same time he checked the engineers’ accounting so that he would not be cheated. In most cases he did not get paid more and would not accept more for this work. He always stood up for the rights of himself and his fellows and always represented their interest against the employer. All this indicates that their well-organized work groups, loyal to each other, already stood closer to the industrial than to the agricultural workers.

Budapest, Teleki Square

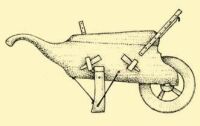

The most important tools of the pick and shovel man were the spade, the shovel, and the hand barrow. He always carried these with him and, as they were his own property, repaired them and adjusted them to the work. The hand barrow is a one-wheeled implement, made of planks, with the aid of which the dug-out earth could be moved to greater or smaller distances. On a flat surface the work was easier and they could do more of it, but help was needed to push the hand barrow up a steep hill. In such cases the man hitched his 10 to 14-year-old son in front of the hand barrow. They often took these children along to working places at great distances. They got no special pay for this, but their input showed up in their father’s income. This was one method of teaching the children the job of the pick and shovel man. In some places there were cart gazdas also, who hauled the dug-out earth on a two-wheeled, square {86.} cart, pulled by one horse to the designated area. Cart drivers and children who could drive horses worked alongside them.

For more extensive construction work, barracks or other temporary lodgings were raised for the pick and shovel men, but in most cases they built their huts themselves before they commenced work. They picked sheltered areas at the bottom of the bank where the work was being done or at the edge of the forest, and used all the raw material they found locally (leafy branches, reeds, rushes, sod, etc.). If they stayed for a longer period, they made a dug-out hut in the ground, resembling structures made by the shepherds and field guards. The labourers usually carried a rush matting with them, which, when spread out on the spade handle, offered protection from both rain and sun. They lit the fire outside the hut in the summertime, but in winter they had to find a place for that too inside.

Everyone saw to his own feeding, the main basis for which they brought from home, chiefly bread, bacon, and various dry noodles, as well as onions. Bacon served for the daytime meals because, since the pick and shovel men worked at time-rates, they kept the rest period as short as possible. Generally they had time for warm food only in the evening, when everybody cooked the tarhonya or lebbencs (pastry cut into big squares) soup in their kettle, with plenty of onion, and, if supplies permitted, with bacon.

Great Plain

Sunday meant a day off in their work. Then, if they lived close, they went home to replenish their food stock and change clothing, to see their {87.} family, and to do some chores around the house. If not, they spent the day cleaning themselves, washing and sewing, because the professional pick and shovel men always tried to take care of themselves even in their difficult situation. If they worked near a settlement they went in there. They looked around and took good note of things useful to them, which is why they played an important role in spreading the elements of material and intellectual culture.

As there were fewer occasions for story-telling, they preferred to tell jokes, narration and personal adventures. Besides the contemporary folksongs, they were already quite familiar with the rallying songs and marches of a political nature. They even added to these and produced rhymed sayings (cf. pp. 507–8). Although not many have been recorded, in the kubikos villages of the South Great Plain people still remember many such rhymes. Most of these lamented the hardship of work, the fight with the elements, the lack of money, the distance from the family, and the hardship of life, as for example:

| The land wrings us dry as dust, |

| The ploughs our palms with sores encrust, |

| Our pants and shirts are bare and mired. |

| The Lord must be god-awful tired. |

| Seasonal Workers | CONTENTS | Agricultural Hands on Large Estates |