| Pick and Shovel Men | CONTENTS | Smaller Groups and Occupations |

Agricultural Hands on Large Estates

We have already mentioned the hired hands or cseléd of the gazda (cf. pp. 63–4), but in the manors of the large estates there lived in much larger numbers the various strata of agricultural hands, also called cseléd, totally defenceless and in very difficult material circumstances. Their system developed in a basically similar fashion throughout the linguistic territory, since the large estate organization also developed in a uniform way (cf. pp. 505–6).

The steward ran a large estate, while the details were directed by the bailiffs (ispán). The gazdas and the overseer carrying a cane (botos ispán) directly controlled the agricultural servants, day labourers, and seasonal workers under the supervision of the bailiff. The bulk of agricultural labourers were the béres, who worked with the oxen, and kocsis, who drove the horses. Their leader was the first béres and the first kocsis respectively, who guided the work directly and got two or three quintals (100 kg) more produce annually for this.

Agricultural hands were always hired by the year, and if they did what was asked, their engagement was extended for the following year. However, if any objection was raised against them, among which talking back was regarded as the most offensive, then they could not stay. In such a case they got a few days to try to find a job on the neighbouring estates. But if word got around that they were disobedient, that is, that they stood up for their rights, then they would not be hired anywhere, and at the end of the year the estate removed them by force, if need be, from their dwellings, so they and their family had to seek refuge with some relative who lived in the village, until they got a job somewhere.

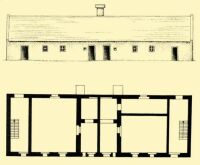

General. Beginning of 20th century

The form of the agricultural hands’ dwelling was very similar over the {88.} entire country from the beginning of the 19th century. In the earliest form, four rooms opened onto one great kitchen and in each room two families were quartered. This meant that often more than fifty adults and children lived together. Later only one family lived in a room, and occasionally only two rooms opened onto the kitchen, but basically the institution of the common kitchen survived right up to 1945. Across from the dwelling the pigsty and hen house were placed, and where they permitted the keeping of cows, the stable. In many places the labourers also got a small field of arable land, a little over half a hectare in size, on which they usually planted potatoes and maize, since this made it possible to keep poultry and pigs.

The quantity and content of the agricultural hands’ annual payment in kind differed significantly according to time and place, so we shall simply indicate its constituent elements. Its most important part was the 12 to 16 quintals of grain (wheat or rye), usually measured out quarterly. Added to this was a definite amount of money, which in value was always significantly less than the price of the grain. Usually they received a pair of boots, later on a pair of brogues, some salt, and according to the natural resources of the area, fuel for heating. To this was added in the older times the keeping of a cow at the estate’s expense, a custom that ended in many places between the two world wars, a certain amount of land, and perhaps hemp and vegetable gardens. The women cultivated these with the help of the children.

There was a strict order for the work both in summer and winter. Reveille in spring was at three to four o’clock in the morning. The béres saw to the stock first of all, then he could go back for a brief time to eat breakfast, after which the carts were driven together to the field. Here the tasks to be done were determined exactly. Work was interrupted by the lunch break, after which it continued until late afternoon. After returning home the animals needed to be cleaned, fed and watered. This {89.} meant that they got home around 8 o’clock, too late to be of any help in the work at home.

In winter the reveille bell was rung later, but even then they were given some kind of work. This is when they hauled the crop to market, to the railroad station, and over long distances. They had to repair carts and farm tools, turn the wheat over in the granary, shell the maize, and cut down and haul the trees from the forest. Still there was more time left for conversation, when in the barn the men welcomed a chance to tell both “true” stories and fairy tales.

Sunday did not excuse the agricultural hands from work, since they had to take care of the stock from morning to evening even then. They tried to help during the day in cultivating and harvesting their land allowance, but in most places the landlord insisted that the labourers go to church and kept a vigorous eye on them. However, Sunday still meant some easing of things. This was the time when the young people got together for conversation, singing, and sometimes even for a little dancing. The farmstead and the manor of the estate were usually located far from the village, so that they could not have had much contact with it. Besides, the villagers looked down on the agricultural labourers and did not welcome them, so that most of them spent their lives isolated from the village. Consequently the number of illiterates among them was considerably higher than in the villages, although in some places, and especially in the 20th century, the estates established schools.

The traditional culture of the agricultural hands was largely in harmony with their surroundings as a less colourful version of it. The furnishing of the dwellings consisted of the same pieces of furniture, but they could not afford painted furniture. The traditional way of arrangement was pared down by merciless necessity. They gave up folk costume soonest, and their diet was a poorer version of the villagers’. Usually they married among each other, and they tried to celebrate the wedding as festively as possible. They clung very much to their traditions and kept many old beliefs for a very long time. Perhaps this explains the fact that in the 20th century various religious sects made great progress among them, while at the same time, because of their defencelessness and dispersion, we can hardly find a trace of organizing activity in the defence of their own interests.

Among the agricultural hands of the large estate, a special place was due to the liveried coachman (parádéskocsis) who drove a carriage of the landlord or the steward. The herdsmen (pásztor) of the estate also belonged among the servants, but because of their higher wages and wider authority, they did not mix much with them. The highest rank among them was given in most cases to the cattle herd (gulyás), who frequently inspected and directed the work of the rest of the herdsmen. The hunter and the forester were also paid in kind, but their tasks separated them completely from the rest.

Beginning with the last quarter of the 19th century, the large estates began to use various power machines. Thus, alongside artisans–the blacksmith, cartwright, etc.–now mechanics and locksmiths also appeared. The artisans received a higher salary in money and in kind than all the other labourers, and were called by the title úr, “mister”. {90.} Artisans did not share with anyone their independent house. They could work for other people for cash, and all this assured them a higher standard of material comfort in comparison to the agricultural labourers. Most of them already had little in common with the traditional culture.

| Pick and Shovel Men | CONTENTS | Smaller Groups and Occupations |