| Southern Transdanubia | CONTENTS | Dwelling Sites of Upper Hungary and the Palots Region |

Western and Central Transdanubia

We can include the entirety of Western Transdanubia, the Balaton region, and the Bakony in this area, a varied, hilly, slightly mountainous, forest-covered region, producing grain at some places and, more importantly, grapes on its gentle slopes. It is among the most beautiful regions of the country. The climate and vegetation of its western section reflects the proximity of the Alps, while its huge walnut and chestnut groves bring to mind the Mediterranean.

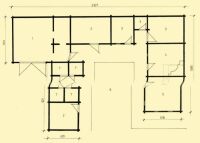

Szalafő, Vas County. 19th century.

1. Barn. 2. Stable. 3. Pantry. 4. Kitchen. 5. Room. 6. Manure heap. 7. Pigpen

Szentbékkála, Veszprém County

This region is characterized by tiny villages huddling near each other and by small towns, most of which preserved their continuity even under the Turks and some of which, furthermore, never came under permanent rule. Current research has failed to find a trace of the double inner-lot settlement. On the other hand, this region is characterized by {178.} the line of scattered houses, threading mostly along the ridges of hills. Originally the plough fields lay adjacent to the houses. The majority of the settlements are agglomerations, a large number of which became street-type settlement later. These settlements have the longest historical past in the north-western areas.

The building material of the houses was primarily wood in the southwest, although this was for a long time eclipsed by stone north of the Balaton (cf. Ill. 9). People mostly used thatch for the roofing of the houses, except that around the Balaton reed was used everywhere. Reed-thatched houses can still be found in the region today. The purlin roof supported by scissor beams was always a basic way of constructing the roof in this region even in the historical past.

One-unit houses still occurred at the end of the 18th century, the enormous size of the room sufficient large for the entire family to live together. Here an open fireplace was used and an oven, which was of a man’s height. They called this the smoky house (füstös ház), because it {179.} did not have any kind of device to divert or catch smoke. It was related in shape to those of the alpine regions. A pantry was attached to this in many places, so that the fire remained in the smoke house. The pantry was a smokeless, cold room, while the “smoke house” continued to be a smoky, warm room. The problem of heating the room was solved first with an oven, later with a tile stove. This change occurred only after the problem of diverting smoke was solved by means of a chimney, and the tile stove could be stoked from the inside. This great change took place during barely one and a half century and altered the one-unit smoke house into a two-roomed smoke-kitchen house. This path was essentially followed not only by the wattle houses of Göcsej, Veszprém, and the Rábca region, but also by the porticoed, pillared, proud stone houses of the Balaton region.

Göcsej. Early 20th century.

1. Fenced house. 2. Well. 3. Place to chuck wood. 4. Elevated pantry. 5. Manureheap, back-house. 6. Straw stack. 7. Oats. 8. Heap of gravel. 9. Hay-stack. 10. Barn

The typical fenced house (kerített ház) of Göcsej developed from this one-unit house. The first step was taken when a third room was built onto the two-unit house. The rooms of young couples did not stand separately any more, but were attached to the existing building, although in such a way that the door of every room opened to the outside so they did not need to pass back and forth from one to the other (cf. Ill. 11). The one or more stables, the pigpen and the chicken-coop adjoined the dwelling rooms, leaning against them. A few sheds, less frequently a barn and granary room, surrounded the yard, which generally speaking was never larger than 100 to 200 square metres. It was shut off in front from the street side by a high fence and a gate, which was always carefully locked for the night. Usually the larger form of buildings, such as the barn, granary room, and separate pantry (kástu), were not built into the fenced house. Similarly, they always dug the well at another part of the holding (cf. Ill. 1, 2).

Balatonhenye, Veszprém County. 19th century.

1. Room. 2. Kitchen. 3. Pantry. 4. Stable

Kővágóőrs, Veszprém County

Balatonzamárdi, Somogy County

The most ornamental part of the houses of Göcsej is the gable made of ornamentally sawn, carved, and painted boards which was protected by the front of the roof. Usually a large cross was cut in the centre of the design and, to the left and to the right of this, by the attic window, open-work flowers were sawn with curving stems growing out of clay pots. The pillars holding the façade were also carved very richly. All this was painted in white, blue, and red, and the free area between the flowers was enlivened with colourful dots. The blinding whiteness of the wall {181.} underneath further emphasized the painted carvings and sawn ornaments.

The largest region of stone architecture is north of the Balaton. The houses accord with the forms discussed above regarding ground-plan of the room, kitchen and pantry and their separate entrances. A specially decorative feature is the colonnaded portico, extremely varied in form and reflecting different European stylistic trends. Although these existed also in other parts of the linguistic territory, principally to protect the main wall and entrance of the house, because of the many possibilities stone architecture offers, it was in this region that the most beautiful and well-proportioned porticoes developed. The good artistic effect is increased by the plaster ornamentation of the façade, richly inspired by the Renaissance, Baroque and in some cases, by the Neo-Classic styles.

The most common farm building in the entire area is the kind of barn called torkos pajta. This, too, varies by region in building material. It may be made of log, of wattle, or, as the house, of stone. A typical building of the Göcsej and Őrség is the usually one-level, rarely two-level kástu, a pantry building that was used also to store grain and as the workshop of the farmer (cf. Fig. 50, Ill. 83).

| Southern Transdanubia | CONTENTS | Dwelling Sites of Upper Hungary and the Palots Region |