| Western and Central Transdanubia | CONTENTS | Dwelling Sites of the Great Plain |

Dwelling Sites of Upper Hungary and the Palots Region

Upper Hungary includes the mountain area from the river Garam to the Hernád, and in some traits as far as the Bodrog river, extending to the Slovak linguistic boundary to the north, and entering into the steppes of the Great Plain to the south. This dwelling area is uniform, although the north-south running river valleys and the watersheds divide its regions. The soil and the natural endowments are mostly poor, and therefore necessity has preserved many ancient features.

Ájfalucska, former Abaúj-Torna County

Alsóborsod, Borsod County

Borsod County

Márianosztra, Nógrád County. 20th century.

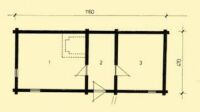

1. Room. 2. Kitchen, called pitvar. 3. Pantry

{183.} The type of divided settlement can be found not only in flat areas but also at the foot of the mountains, or in some places, even in mountainous regions. As the Turkish rule reached only until the lower border of this area, the form of village settlement preserved a number of medieval characteristics. Many agglomerate villages exist, some of which loosened up and developed street systems only in recent times. We can also find good examples of the “spindle” (orsós) type of settlement.

The Palotses built out of wood until the time that the forests thinned out. They either built their walls from plain logs or used corner-post construction, or else they lowered thicker planks into the grooves of perpendicular beams. Only in the last hundred years have clay buildings become accepted and eventually widely used, out of necessity. In rare cases, the roof structure is of the purlin type, but more frequently of the rafter type, and is covered almost exclusively with straw thatch. The Palotses were always outstanding craftsmen in thatch work.

As far as it can be traced historically, the hearth was built into the room and was stoked from the inside. A small bench in front of it was used for cooking and baking over an open fire (cf. Ill. 68, 69). Such large, flat-shaped hearths with the open fireplace may be found towards the north, among the Slovak population. On the other hand, the spread of the stack-shaped oven came to the north in the 19th century from the Great Plain. The “cold porch” (hideg pitvar), without a fireplace, was attached to the house and was used more or less as a storage room. When the fireplace was moved to the porch, a pantry was attached to the first.

The Palots house, with its size and partitioning, was suited to the extended family, often consisting of 25 to 30 members. The family stayed together along the male lines, under the leadership of the farmer; that is to say, the grown sons brought home their wives and lived together forming a single economic unit. The family stayed together in the extraordinarily large-sized room all day in winter, they cooked and ate there. But the room served as the sleeping place only for the men, because the women along with the small children slept in the unheated chamber that opened from the porch. Usually mosquito netting separated the beds from each other, which gave protection against mosquitoes and flies in the summer and also against the cold in the winter. The young men preferred to sleep in the stable and in the barn, in the attic of the house, or in the hay during the summer.

Among larger farm buildings, the most important is the barn, which had three sections in rich households, two in poor ones. Among the smaller buildings let us mention the pigpen (hidas), present in every yard. Such were also made for sale and shipped in a dismountable form to more southerly regions.

| Western and Central Transdanubia | CONTENTS | Dwelling Sites of the Great Plain |