| Dwelling Sites of Upper Hungary and the Palots Region | CONTENTS | Dwelling Sites of Transylvania and the Székely Region |

Dwelling Sites of the Great Plain

This area comprises the largest territory. As far as architecture is concerned, the Great Plain extends far toward the south, and also seems to reach the Little Plain through the north-eastern corner of Transdanubia. This landscape is completely flat, margined by gentle slopes. In the past, flooded plains and permanent marshes occupied its major part, while in the Nyírség, and between the Danube and Tisza, sand prevailed. {184.} All these natural factors, along with the cold winters, extremely hot summers, and the lowest rainfall in the Carpathian Basin, influenced architecture significantly.

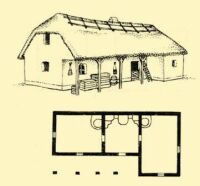

Bihartorda, former Bihar County. Early 20th century

The Hajdú towns of the Tiszántúl represent the classic form of the double inner-lot type of settlement. Few villages remained on the area once occupied by the Turks, but some of them were resettled. Therefore villages with regulated streets are numerous, since new settlers had to build in such an order.

The history of this dwelling region is known primarily from archaeological excavations. Houses from the 10th to the 13th centuries that were sunk half into the ground have been discovered, consisting of a single large room of 10 to 12 square metres. In one case an oven was found in the corner of the house, dug into the ground on the same level as the floor, though in this period the majority of ovens were built outdoors, outside the houses. But archaeologists can show village houses from the 13th century that had two rooms and were rectangular in shape. One of these may have had wicker walls standing mainly above the ground. More and more data testify that from this time on the partitioning of the peasant houses into two and later three rooms began.

Komádi, Hajdú-Bihar County

Bihartorda, former Bihar County. Early 20th century.

In the kitchen, note the fireplace on a bank, in both rooms a round oven to be heated from the kitchen, one surrounded by rods for drying clothes

Karcag-Berek, Szolnok County. 1851

The walling material of the Great Plain house is primarily clay. The wicker wall appears to be earliest, followed by the stamped mud-wall, {185.} and most recently the adobe wall which has eclipsed everything else. The roof structure is of the purlin type, supported by two, perhaps three forked uprights. Reed was used first of all for covering, but in some places they substituted rush and sedge (cf. Ill. 14). Straw roofs also occurred, but only in a pressed version, since treading was the basic method of threshing grain and they possessed only pressed straw.

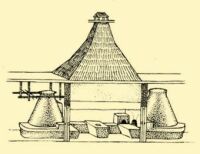

In regard to the fireplace installations, it is noteworthy that the oven built outside but stoked from the inside of the house survived in many places, among others, on the Little Plain. Otherwise, the problem of channelling the smoke was solved here at the earliest time. The central partition unit of the house was divided into two parts. A skirted chimney, usually made of wicker and plastered, reached above the roof through the attic and channelled out all the smoke from the house. Open fires were used on clay banks in the kitchen, or cooking was done in openings along the edges of the banks. A large oven, round or rectangular or of some other shape, was built in both rooms, and stoked from the kitchen (cf. Ill. 67). The replacement of the oven by a stove did not happen, because the available heating fuel (reed, straw, maize, and sunflower stalks) preserved the oven until the most recent times.

Milota, former Szatmár County. 19th century.

1. Room. 2. Kitchen (pitvar). 3. Open porch

We are going to mention separately two smaller areas within this large region. One is the Little Plain, which lies along the western branch of the Danube, and to the south and north of it (Czechoslovakia) and can largely be followed to the Hungarian linguistic border (Zobor region). In the three-unit house, the doors of the two rooms opened onto the porch. The oven was located outside the building and its mouth opened from the back wall of the kitchen. The stoke-hole of the rooms opened into the kitchen, and they built a bank in front of it. So far, the type of fire bank placed in the centre of the kitchen has not been found in this area. The rooms were heated with tile stoves until the most recent times, but large-sized low ovens also occurred in some places.

The other small area under discussion lies in the north-eastern corner of the Hungarian linguistic region, in the valley of the Tisza and its tributaries. Wood has a greater role in building, manifest in fences, gates, granaries and belfries. One characteristic of architecture here is the colonnaded portico that surrounds the house in some cases on two, and {186.} in others on three sides. Numerous versions of the hearth with a perpendicular chimney are noteworthy among fireplace installations. Many characteristics show that the architecture of this area is a transition in the direction of the Great Plain, the Palócföld, and, most of all, toward Transylvania (cf. Ill. 4–6), with which the ethnography of this area has much in common.

Most of the farm work was done outdoors in the Great Plain, so no barn is present in this region. Barns occur only in the flat areas bordering on the mountains, as well as in the two small regions mentioned above, as a result of an attempt at intensive farming. In the Great Plain yard, we usually find the stable, smaller pens, cart and chaff sheds, as the extension of the house, only with lower roofs, and perhaps granaries and pits.

| Dwelling Sites of Upper Hungary and the Palots Region | CONTENTS | Dwelling Sites of Transylvania and the Székely Region |