| Harvesting and Harvesting Customs | CONTENTS | Hoed Plants |

{210.} Treading and Threshing

Grain on the stalks that had been tied into sheaves was stored in the barn, if such existed. In the Great Plain and the eastern part of Transdanubia, they stored some of it in the open air in stacks (asztag), and some they trod out immediately. They carried it to the storage place on carts, stacked in one of the two ways known in the Carpathian Basin. In the Great Plain and generally in flat regions, two long poles are fastened onto the sides of the cart and the sheaves put on the cart so lengthened, with the ears facing inward. The sheaves are roped to the two ends of the poles. In mountain areas the carts are longer and their sides higher. In these areas cart ladders are not used, but a hay pole, nyomórúd, is laid on top of the sheaves and fastened to the four corners of the cart, so that the harvested grain cannot slide apart even if the cart should turn over. We find equivalents of the former towards the east, and of the latter rather towards the west.

From the Middle Ages on there were two processes for separating the grain: treading out (nyomtatás), which was done by animals, and threshing (cséplés), carried out with a flail. The former process mostly relates to South-Eastern Europe, while for the latter we must look to Central Europe. Treading out is the method used in the extensive agriculture of the Great Plain, a method further reinforced during the economic decline caused by the Turkish rule. Flail threshing prospered in the mountain and hill regions. They preferred to tread the grain in the eastern half of Transdanubia during the middle of the last century, while threshing with a flail was more general in the western half.

Átány, Heves County

Mezőkövesd

Kardoskút, Békés County. Early 20th century.

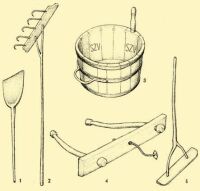

1. Shade for winnowing. 2. Rake for gathering chaff. 3. Noggin or bushel. 4. Wooden implement to draw together the threshed cereal. 5. Implement to shove the cereal together

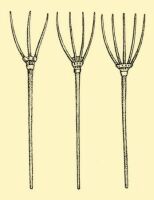

1. Szegvár, Csongrád County, 1896. 2. Kémér, former Szilágy County, 1942. 3. Doboz, Békés county, 1934

{211.} The threshing floor used for treading out was mostly beside the ploughed field, or at some other place in the farmyard, the threshing yard, or at the loading place outside of the village (cf. Plate VII). Weeds were cleared from an area, which was in the shape of a circle or ellipse, then it was dug up and clay soil carried onto it. They spread chaff and straw on it and watered it whilst trampling it by horses or perhaps by carts. When the ground became smooth they scattered chaff and straw on it so that it would not crack in the strong sunshine.

Kardoskút, Békés County. First half of 20th century.

a) Turning around the heap of crops. b) Horses treading out the crops and men carrying away the empty straw. c) Winnowing, dividing the cereal from the chaff d) Collecting the cereal in a heap called garmada

Óbánya, Baranya County

{212.} They “made the bed” (beágyazás) for treading on the completed threshing floor, that is to say, they covered the entire area, thickly and evenly, with loosened sheaves. They then led the horses on it, 2 to 8, according to need and availability. Because the work was hard both for horse and man, they relieved them if it was possible. In most cases the whip-man (ostoros) stood in the centre and drove the horses (less frequently oxen) in a circle, adjusting the length of the tether, so that the horses walked on all parts of the bed of grain equally. Another method was to set a post into the centre of the threshing floor, and the rope of the circling horses wound around it. Thus they moved in decreasing circles towards the centre. In some places, carts were also used for treading out. They yoked the horses and drove the carts around on the grain. When the grain on the stalk had broken down sufficiently on the bed of grain (ágyás), it was turned over with a wooden fork and shaken so that the {213.} seeds would fall out of it. They repeated this process three times, and only then did they fling the straw off. They pushed the chaff and seeds to the edge of the threshing ground in a heap (garmada), and waited for a suitable wind for winnowing.

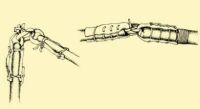

a) Magyarszerdahely, Zala County. b) Szalonna, Borsod County, 1930s

Threshing with the flail was always done inside the settlement, in the yard or in the barn. In both places they would prepare a square threshing floor, stamp it down, and plaster it over, so that not a single grain should be lost. The flail (csép) consists of two parts, the handle (nyél) and the souple (hadaró), which was half as long. The two are linked by a thong in such a way that the souple can rotate. In most cases everyone makes this tool for himself, and there are always a few pieces around, hanging on the beams of the barn. They lay down two rows of tied sheaves with the ears facing each other. They thresh these, then turn them over with the handle of the flail and thresh the other side as well. At this stage the ripest seeds fall out, and are stored for sowing. Next they untie the sheaves and carry out a fresh, more thorough threshing, and after they have beaten out every seed they brush the straw off with the help of the flail. They first clean the chaffy seed with a rake, then collect the seeds in a corner of the barn. If several people are doing the threshing then they beat rhythmically, the rhythm changing according to how many people are working together. The number of the threshers can be told from a distance by the noise of beating.

Szentgál, Veszprém County

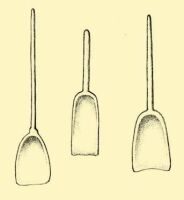

The seeds left after treading out or threshing have to be cleaned of {214.} chaff and bits of straw. The most general method is winnowing (szórás), which was done in a different way in the Great Plain and in the hill and mountain regions. They waited for the wind on the plain, and when it came they threw the grain up against it with a long-handled wooden shovel. The heaviest, ripest seeds could easily fly against the wind and thus reached the ground the fastest, while the refuse grain and the chaff fell at the winnower’s feet. Another man stood at the side and tried to drive off the remaining waster from the clean seeds with a wide wicker broom.

a) Szegvár, Csongrád County. b) Oltszem, former Háromszék County, c) Füzér, former Abaúj County. Late 19th century

It is relatively easier to create a draught in the barn by opening the two doors, located opposite each other. Here, between the doors, they threw up the chaffy grain in a half circle, in the direction of the wind, but with a much shorter-handled shovel. In some places they did this whole process sitting down and with a very short-handled wooden shovel, both granary doors remaining shut. In this case only the resistance of the air does the job of winnowing.

Even after winnowing, the grain was still not completely clean. Therefore, they poured it into a trough and picked out the visible dirt, the bits of soil, by hand, before taking it to the mill. In some places they washed it thoroughly and spread it out to dry.

The cleansing processes described above were closely connected with treading out and with flail-threshing of grain, and disappeared with the mechanical threshing and winnowing of the grain.

| Harvesting and Harvesting Customs | CONTENTS | Hoed Plants |