| Treading and Threshing | CONTENTS | Processing Cereals |

Hoed Plants

Hoed plants, the majority of which were imported from America, moved into plough-land cultivation from the 17th century. These gained an ever-growing significance both as fodder for the animals and as food for the people. Together with the new plant culture, new knowledge, tools and procedures also became naturalized. At first the new plants were grown in the garden, but soon they were moved out to the ploughed fields, where they first of all took over the place of the fallow field and, in this way, advanced the break-up of the rotation system and in some places even caused its termination.

The potato (Sloanum) is one of the most important food staples of our century, which today occupies about five per cent of the country’s cultivated land. It appeared on the plough lands in the 18th century, but did not spread easily among the peasants, because its method of cultivation was contrary to methods with which they were familiar. The lean years of the 19th century, in conjunction with vigorous urging by the authorities and landlords, helped its domestication. Its propagation was also advanced by the fact that in most places they did not have to pay a tithe on it. Its regional locations developed at this time (Nyírség, Somogy, Vas counties), where the plough lands planted with potatoes exceed more than ten per cent of the total cultivated land. Producing for the market began in these areas already at the beginning of the 19th century. Planting is done in the spring with hoes, planting sticks (cuca), or by following the plough and planking it into every third furrow. It is hoed two or three times, then in the autumn dug out from the ground with a flat or, in some places, a two-forked spade. During the 19th {215.} century, especially in regions where potatoes were grown in large quantities, they were taken up with the plough, which was used to split the drill. They were stored in prism-shaped pits, covered with straw and soil as protection from frost, and to keep them until spring. Smaller quantities were stored in cellars, or in pits in the yard or garden.

Bercel, Nógrád County

Today the sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) is the most important oil-supplying plant in Hungary. Its proliferation is even more recent than that of the potato. Although we can find drawings of it in 16th-century books on botany, it was treated at that time as an ornamental plant in the gardens of the upper nobility. Familiarization with its excellent oil at the end of the 18th century suddenly boosted its popularity. At first it was planted in the garden around the house, and only during the first half of the 19th century was the cultivation moved out to the plough land. Its larger-scale production began only in the second half of the century, primarily at places where, for religious reasons, people did not cook with pig lard during a large portion of the year but used oil instead. On the plough fields it is still planted on the borders of potato and cornfields, especially on peasant farmsteads, and its planting in whole fields has come about only during our century, even on the large estates. They {216.} planted it in larger quantities in the Nyírség, in the southern and south-eastern part of Transdanubia, and in between the Danube and the Tisza. The cut-down heads were carted home, dried in the granary, on the porch, or on an out-of-the-way part of the yard, then the seeds were beaten out with sticks and beaters. This is usually an evening’s work done with help, but it is also a time of entertainment that gives a chance for story telling and singing.

Szeged. 1930s

The paprika (Capsicum annuum L.) is a spice originating in America, without which it is impossible to imagine the Hungarian kitchen. It occurred already in the gardens of the nobility in the 16th century, but it was then grown only as a flower or medicine. It became popular among the peasants in the 18th century. In all likelihood this wave may have come from the south, perhaps through the Bulgarian gardeners or through the Catholic Serbians who also wandered in from the south. Two significant cultivation regions developed in early times, which exist until today. One is at Szeged and its surrounding region, and the other is north of these around Kalocsa. There is one significant difference in the method of production at the two places. At the former they grow the seedlings in hothouses and then plant them outside, while at the latter they throw the paprika seeds directly into the ground and thin them out after they have come up. The paprika is a very delicate plant which needs to be hoed two or three times. It also needs a lot of water, especially until the seedlings have taken root. In the past they began to pick it after the birthday of the Virgin Mary (8 September), but recently they have started somewhat earlier, at the end of August. The gathered paprika is first dried for a short time, then strung up. This is communal work reaching late into the night, and gives a chance for entertainment. The core of the completely dried paprika is removed, broken up, cleaned, then ground in a wooden mortar (külü) operated on foot, or in the case of larger quantities, in a paprika mill with a grindstone.

Tobacco (Nicotiana L.) had already become known in Hungary by the 16th century, but at first it was used only as medicine. The Turks also had a role in its dispersion. Decrees prohibiting smoking became increasingly frequent from the 17th century on, but these led to no results. At the beginning of the 18th century, tobacco was grown not only in gardens but on the fields as well, and tobacco regions involving certain villages and regions came into existence. The smoothing of tobacco is also work done in company, like the jobs mentioned above. The growers of paprika and tobacco, because the plants require special skills, developed into an occupational group, but while the former were assured a relatively good livelihood, the tobacco growers, who cultivated land rented from the large estates, for the most part barely surpassed the living standards of the farmhands of the large estates.

Botpalád, Szabolcs-Szatmár County

Maize (Zea mays) had already appeared in production by the first half of the 17th century in Hungary. This undemanding plant spread rapidly and quickly found its way from the garden to the fields, especially because for a long time farmers had to pay no tithe or ninth for it. The area planted increased more and more, until today it has approached, and at times even surpasses, that used to grow wheat. Today one quarter {217.} of the entire Hungarian sowing area bears crops of maize, but in certain regions it exceeds 30 or even 40 per cent.

The cultivation of maize differs greatly from that of other, earlier known cereal types, although at first they tried to adjust it to others. They simply threw the carefully selected seeds in the ground and ploughed over them, or sowed them on the ploughed field and harrowed them in. They generally put the date of sowing on St. George’s Day (April 24). There are several superstitions attached to the sowing. Thus, in the southern part of Transdanubia, the first seeds were sown with closed eyes, through the slit of the skirt, so that the rodents should not find it. In the Nyírség, smoking was prohibited during sowing, to keep the blight away from the crop. In Szatmár County, the belief was that if you looked into the sun during sowing, then your wish for lots of red ears among the crop would be fulfilled. Egg yolks were eaten at the completion of the sowing in Kemenesalja, so that the ears should be all the more yellow.

Sowing in rows or drills replaced scattered sowing in the 19th century. They used a four-toothed marker, with which they marked the maize rows on the ploughed field. Along this they threw the seeds into holes pierced with a stick or made with a boot-heel, and covered them with the feet. Two people worked together when sowing with a hoe. One lifted the soil with the hoe, the other threw 3 or 4 seeds under it. Many people eliminated the drawing of lines by dropping the seeds into every third furrow at ploughing, which was covered by the plough during the next turn. To make sowing in rows easier, various sowing devices, fastened onto the plough beam, appeared during the last century, made from wood by handy peasants or from iron by the local blacksmith.

{218.} During the 19th century they hoed the maize once for weeds and once to earth up the stalks. The first hoeing took place shortly after the maize came up, when only the most strongly developed plants were left growing in one cluster. Earth was hoed up around the maize stalks immediately before harvesting. Many people opposed this procedure from the second half of the century, and it indeed ceased on the large estates. However, in the peasant farmsteads this hoeing up survived in most parts of the country till the period of collectivization, because they believed that the stalks supported in this way were less likely to be bent or knocked over by the wind. The horse hoe (lókapa) appeared at the beginning of the last century. Its earliest form was actually similar to a symmetrical plough of smaller size. It only showed up at larger peasant farmsteads in the second half of the 19th century, while it never really reached the poor peasants. The superstition that palms rubbed with soil from the first stroke of the hoe will not blister is linked with hoeing in Göcsej. In southern Transdanubia they hoed during the last quarter of the moon, because it was thought that the weeds could be better destroyed then.

Mezőkövesd

The fact that it is hard to see far into the tall, growing maize, was favourable to thieves. Therefore, from the beginning of the ripening the field keeper stayed in the fields all the time. He raised by his hut a 4 to 5 m high pillar similar to those of the herdsmen, on which, to make climbing easy, he fastened some rungs crosswise. Thus he could survey {219.} at any time the maize he had been entrusted to guard. Field keepers were paid in maize, getting 30 to 100 ears for each cadastral acre as well as a part of any thief’s fine. Otherwise they had to pay for all damage that befell the crop. Keepers came out of the ranks of older farmhands and herdsmen.

Békés County. 1930s

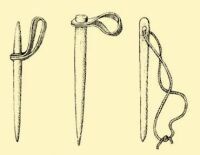

Maize generally ripens in September, which is when the picking takes place (cf. Ill. 34). Two forms have been known from the earliest times, depending on how the ears are broken off the stalk, whether with or without the husk attached. In the latter case, they use a small wooden opener (bontófa) that can be fastened to the wrist, with which they rip open the husk and twist out the clean ear. The shape of such wooden openers corresponds with the ones used at one time by the American Indians. Numerous data indicate that it may have become part of the Hungarian peasant’s stock of tools during the turn of the century through migrants who had been to America. Originating from the large estates, clean picking spread increasingly.

The other method is to pick the ears with the husk on and carry them home in carts. The cobs were piled into big heaps in the yard or barn and the relatives and neighbours were called over for the evening to help husk them. This counted as the most pleasant work and entertainment during the mild, early autumn evenings. Husking cobs is important work and has to be done urgently, because the ears cannot be kept long in their husks without danger of spoiling. Much tradition and many customs are connected with husking. Thus, a special significance is given to those who find a red ear: it means that the lucky young man or girl is going to get married next year. Red ears hung at the front of the house signal that there is a marriageable girl inside.

Csongrád County. Late 19th century

Rarely is masquerading left out of husking, when the young men try to scare the girls. They put on white sheets, paste on beards and moustaches made from maize silk, and perhaps carve a death’s head or mask from a pumpkin. They go thus from one place to another. Songs are likely to come forth during husking, especially songs connected in some way with maize. This gathering is an excellent opportunity for story telling, although not so much for the long fairy tales as for the scarey, superstitious legends which are listened to in great silence. Story telling is the job of the older folks, who are often invited only for that purpose. Usually fruit, boiled potatoes, and corked maize sprayed with poppy seeds and sweetened with honey is served to the helpers. Sometimes they also have some sweet pastries and a few glasses of wine. When they have finished the work, they dance to the sound of a zither or, earlier, of a bagpipe. At large huskings they even hired a gypsy musician. The dance rarely lasted past midnight, since next day at dawn picking had to continue.

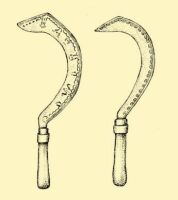

Not only the ear of maize was made use of but the stalk of the corn as well, which counted as a medium-grade fodder. During the first half of the 19th century, in many places the stalk was left outside, and in winter time the cattle grazed it on the spot. During the second half of the last century the shortage of fodder became so great that it was regularly gathered in. This was done with a sickle, reed cutter, stalk cutter made out of a scythe blade, axe, or hoe, the implement differing regionally or {220.} by the size of the land holding. The stalks were tied into sheaves, which were stood on their ends, stacked in cones, and hauled home during the winter frost. They were placed in the yard or threshing yard, and fed to the cattle by spring. The remaining segments, just like the stump which was carefully taken out of the ground, were the most important heating fuel on the plain from the beginning of the last century.

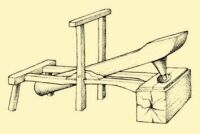

Shelling maize is a winter occupation, with a great many variations. The most simple way to shell maize is by hand if it is dry enough. At other times they rub two ears together, but even more frequently they rub the seeds off with a cob. To make this easier, first a few rows are pushed off with a pointed iron tool. At some places a blade is driven into the edge of a small chair and the ears repeatedly pulled over it, the seeds falling into the basket placed underneath. The sheller, a utensil that fits onto the hand appears to be more recent. Its teeth pick off the seeds from corncob. Shelling chairs, the fronts of which are studded with nails, are based on essentially the same idea. It used to be customary to thresh maize in the south-western part of Transdanubia and in Transylvania. In Transylvania, the threshing basket is also used. When cobs are put into it and beaten with bent sticks or wooden mallets, the seeds fall out of its plank bottom through small holes. Various sizes of shelling machines proliferated from the middle of the last century.

From a comparison of historical, linguistic, and ethnographic data, it appears that two centres of maize growing developed in the Carpathian Basin: one is Transylvania, the other Transdanubia, especially its southern part. The new plant appeared early in both places. Its method of cultivation and use clearly shows that in one place the Rumanians, and in the other the South Slavs may have been the mediators.

Maize replaced in the diet the porridge plants (millet, buckwheat, einkorn, barley) and took over their nutritional role. The role of these plants in feeding animals, principally in the fattening of pigs, was likewise eclipsed. When the practice of fattening for the market increased, from the beginning of the last century, the area of maize sown increased simultaneously. Its role in human diet has since gradually decreased and its use pushed increasingly in the direction of fodder. Today food is prepared from maize regularly only in certain parts of Transylvania and in a few parts of Transdanubia.

| Treading and Threshing | CONTENTS | Processing Cereals |