| Hoed Plants | CONTENTS | Grapes and Wine |

Processing Cereals

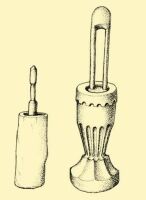

Cereal grains first have to be crushed to prepare them for human consumption. The simplest and most ancient tool for this purpose is the wooden mortar, which is carved out of a single piece of wood. In it the grain was crushed, formerly with a wooden, more recently with an iron pestle. It is still used in the peripheral areas, but at most to crack millet and corn for the chickens, or less frequently to crush poppy seeds or perhaps paprika.

A technically more developed version of the mortar is the large sized külü, which they set in motion by foot or by shifting the body weight. Some had several grinding holes, and a corresponding number of men could work simultaneously. They dehusked millet and buckwheat with these, and used them until very recently for crushing paprika.

a) Göcsej, Zala County. b) Former Bereg County. Late 19th century

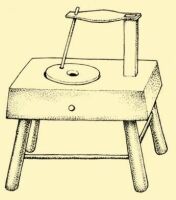

{221.} A faster and more profitable process is the grinding of cereal seeds between two stones. The bottom stone is always fixed, while the top stone can be turned. The grain to be ground is allowed to trickle in through the eye in the centre of the top stone. This simple hand tool, traceable to ancient times, has survived sporadically in peasant households until today. Earlier it was used to grind flour for meal, later on to grind salt and fodder for the animals. Two versions of it are known. In one the handle is fastened directly on the top stone so that it can be brought into motion only with a strong effort. We can find versions of this form from Roman times, and its connections are primarily towards the west. The handle of the other type is fastened to an overlying beam, so that it is easier to use. This method appears frequently among the Eastern Slavs also.

Hungarian grain production, which was large in quantity and looked back over a considerable past, also gave rise to the creation of a long line of mills driven by water, animals, or wind. The word malom (mill) itself and the attached molnár (miller), as well as a whole series of names for parts, are Slavic in origin, and are words which the Magyars may have learned already before the end of the 10th century. The name most likely referred to a water mill, since in the following century (1083–95) a whole string of mills is mentioned in the Bakony. It is probable that mills driven by animals gained ground at a later period, while windmills, which originated in the west and appeared only in the 17th century, really gained ground only during the next century.

Szalonna, Borsod County. 1930s

Two broad groups of watermills can be differentiated in the Carpathian Basin. One is the horizontal type with a scoop wheel, the other the vertical water-wheel type. The former occurs relatively rarely. The wheel turns horizontally in the water, and a spindle rises perpendicularly from its centre, with its top end fastened directly to the upper millstone. Thus the wheel turns the millstone by direct drive, with no intermediate gearing. This type is known in southern Transylvania as well as in the Dráva region, so that its ties can probably be sought in the direction of the Balkan Peninsula.

The vertical watermill can also be divided into two broad groups, one undershot (alulcsapós), and the other overshot (felülcsapós). The former were built on wide, quietly flowing rivers, so that they were also called hajómalom (boat mill). The entire mill and the adjoining mill house were shaped like an ark so that they could be towed to a safe place when the ice flood began. The somewhat smaller store-boat (tárhajó), attached to the boat mill, not only housed the grain to be ground, but at the same time also supported the outer end of the axle of the huge wheel. It was made entirely of wood, primarily of oak, except that the cog-wheels were carved out of hornbeam. The daily output of the boat mill can be assessed at approximately 10–12 ql, which was greater than the performance of windmills but less than that of animal-powered mills.

Szarvas

The number of overshot watermills always greatly exceeded the number of undershot mills, since it was easy to channel the dammed-up water of any little stream from above onto the paddles of the wheels. The watermills were made and repaired by the millers themselves, who were also excellent carpenters. Usually the miller’s family lived in a house {222.} attached to the mill. The miller hired help, an assistant or apprentice, only in larger mills which had several pairs of stones. He collected a duty on the milled grain, and either rendered an account of it to the landlord or redeemed the rental dues for the whole year in one sum.

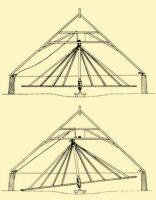

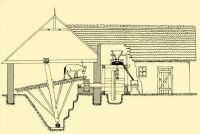

Dry mills (szárazmalom) were driven by animal power and their occurrence in Hungary can be traced all the way to the Middle Ages. Nothing shows their significance better than the fact that 7,966 of them were still operating in the country in 1863, but their numbers were reduced to 651 forty years later. The dry mill consisted of two parts. One was the kerengősátor (turning tent) or horse-walk, in which the horses turned the huge wheel that brought the millstone into motion. The other was the millhouse, where the grinding mechanism was housed and where there was also space for the grain waiting to be milled or for the ground flour. The person wanting to have his grain milled had to provide the turning power, for the miller merely ran the turning mechanism. Usually he had a long time to wait, because the work progressed slowly. The men who gathered from the village or from neighbouring settlements liked to talk and tell stories to shorten the slowly passing hours. Thus the mills fulfilled an important function not only in spreading news, but in spreading certain intellectual traditions as well.

functioning, and when ready to be drawn by a horse.

Szarvas, Békés County. 19th century

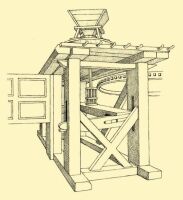

One version of the dry mill was the treadmill (tiprómalom). Its large wheel was clad with sloping planks, on which the animal moved, seemingly climbing upwards but actually remaining in one place. In this way the big wheel came into motion, and by means of cog-wheel gearing it turned the millstone.

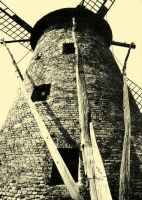

{223.} Windmills (szélmalom) are relative latecomers to Hungary. They spread primarily in the Great Plain in parts of certain regions of Transdanubia. The more primitive form is the post windmill (bakos szélmalom), built on a huge central beam rising perpendicularly from the ground. With its help the mill could be turned in the proper direction to catch the wind. This type of mill is generally used in the Mediterranean region, coming to the western part of Europe perhaps at the time of the Crusades and moving to Hungary from there, but it never came into general use and only a few pictures and notes preserve its memory. In the southern part of the Great Plain (Hódmezővásárhely), there were still in the recent past a few small sized wind grinders that worked on the same principle.

Gyimesközéplok, former Csík County

Kiskundorozsma, Csongrád County

Bakonypeterd, Veszprém County. 1930s

Mekényes, Békés County. Early 20th century

{225.} The windmills that are best known, and of which a few have come down to us, belong to the so-called tower-mill type, the equivalents of which are found primarily in Holland. It is thought that its plans were first brought back by those Protestant students who frequently visited the universities of Holland from the 17th century on. The tower was built of adobe, or more frequently of baked bricks. The millers not only built the wall, but also did the carpentry work, which required extraordinary precision. They joined together the beams, carved the cogwheels, {226.} made the frame of the sail, and ornamented the cover plates of the interior machinery with rich carvings. They divided the structure into several floors. The stones, the driving mills, and storage room were located in separate areas. The four-vaned sail, attached to the roof section on the outside, could be moved, along with the entire roof, to face the direction desired with the help of a long beam from below. The use of windmills lasted longer than that of dry mills. 475 were registered in the entire country in 1863, ten years later their number had increased to 854, and in 1906 the number was still 691. The majority were operating between the Danube and Tisza.

We can also list among the mills the oil presses (olajütő), the various versions of which can be found over the entire linguistic region. They pressed out the oil primarily from pumpkin, hemp, flax, sunflower seeds, and acorns.

| Hoed Plants | CONTENTS | Grapes and Wine |