| Hunting | CONTENTS | Animal Husbandry |

Fishing

The Magyars had lived around waters in their ancient homeland and fishing has been among their most important occupations. A number of fish names (hal, fish; meny, burbot; keszeg, bream; őn, baleen) and names of utensils and erections (háló, net; para, cork; halúsztató fa, wooden fish trough; vejsze, fish weir; horog, hook; hajó, boat), all of Finno-Ugric origin, testify to its role in the past. In the course of their wanderings the ancestors of the Hungarians learned much from the Slavic peoples of the South Russian steppes, especially in regard to fishing. This is proved by words such as varsa (fish weir), and the technical word characteristic of large-scale fishing, tanya (the area of water and shore where the fisherman casts his net). And since big rivers, lakes, smaller streams, and endless swamps favoured this occupation in the new homeland, it has persisted until today. Charters of the 11th and 13th centuries already mention fishermen, who supply the required amount of fish to their lord, and even speak of entire villages that lived primarily from fishing. The profession of fishing was sustained during the following centuries, fishermen having to hand over two-thirds of their catch to the landlord, although they could keep all the smaller fishes. Fishing played an important role in providing supplementary food in the past, since every peasant who lived near water fished, mostly with implements he could handle alone.

The simplest kind of fishing is done with the bare hands. This is the oldest method of catching fish and requires a very thorough knowledge of the habits and bodily structure of fishes. In this method, the fisherman stands against the flow of the water in fast mountain streams and, when he spots the fish, tries to catch it by its gills and throw it on the bank. In standing water the fisherman submerges with open eyes and tries to approach his victim with slow movements. He runs his hand along it to locate its gills exactly. He quietens the thrashing of the caught fish with his other hand, until he can reach the shore.

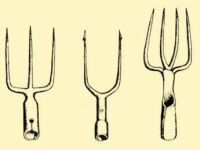

1. Nagyvarsány, former Szabolcs County. 2. Nagykálló, former Szabolcs County. 3. Petneháza, former Szabolcs County. Early 20th century

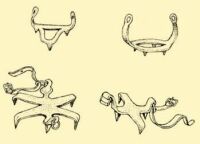

{239.} The fish spear is one of the oldest and most generally used fishing implements, the one-pronged or multi-pronged varieties being known over a wide area. The tip of the prong is bent back, so that it will not tear out of the body of the fish. (If the fish should free itself, it bleeds to death because of the big wound.) The spear-fisher wades into the water, or waits on the shore, but mostly watches from the bow of the boat for the fish to appear. The spear could be used with greater success during spawning, but it caused great damage in the fish stock. Therefore, its use has been prohibited by law since the end of the last century, although its use still occurs even today. It is worked for preference at night. A torch is lit on the bow of the boat, and the fish that are attracted by the unusual light are an easy prey. The accessory to this method of fishing is the short-handled, curved gaff, with which the larger and strongly thrashing fish are lifted into the boat.

Kopács. former Baranya County

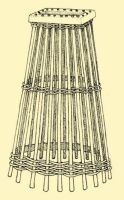

A characteristic tool of the small fisherman who works alone is the groper, a basket woven up out of twigs for catching fish, used in swamps, flooded areas, and along river banks, in water no deeper than one metre. Its oldest forms were woven from wicker, and more recently they have covered its frame with netting, and even rigged up a long handle on it, so that the man wading in the water can reach forward with it and in this {240.} way does not scare off the fish. A bottomless wicker basket, for example a beehive with its end cut off, is suitable for this method of fishing. It depends largely on chance, the fisherman pushes the groper here and there, and if he feels the impact of a fish, he reaches inside and lifts it out by hand. This simple form of fishing is known in many places but we must look primarily towards the east for its exact equivalents.

Békés County. 1930s

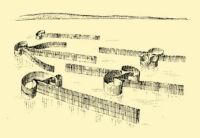

Trap fishing relies on the habit of fish to keep their direction. That is, once it has started off in one direction, a fish changes it only if it runs into some obstacle. It feels the obstacle with its nose, because it is seeking a passage, a way out of it. The fisherman counts on this behaviour when he sets up a fish weir. This is usually made of reeds and is raised at least half a metre above the water. The mouth of the fish weir drives the fish towards the winding funnel, which is built so that the fish can not again escape from it. Periodically, the fisherman lifts the fish out of the funnel and into the boat with the aid of the scoop. In Székelyland they block up the fast running mountain rivers and larger streams with dams made of stones (cége), from which the fish can escape only through the opening left in the centre. This is where they place the fish trap, the fish weir, usually made from wicker. Although the fish forces itself through its small opening, it cannot get out again. At other places they make the enclosure out of thick gates, the space between which is closed by wattle work, and with this they direct the fish toward the winged, netted fish weir that is set up at the opening (e.g. Bodrogköz).

Lake Balaton. Late 19th century

Fishing by lifting relies on the fish’s attempt to escape danger downward or sideways when it senses it, and, as it is swimming above the net that has been lowered into the water, the fish gets caught. The dipping net is the characteristic tool of the small fisherman who fishes alone, and would not be used much by a professional fisherman. They tie two hoops across and to the end of each they fasten the corner of a square net. They fish with it mostly from the shore, rarely from a boat. The fisherman watches when the fish appears above the net, so that by lifting the net he can capture it. This method of fishing is related to enclosing. In this case they fish from the seat raised above the weir opening, because it is easy to catch the fish as it passes through.

River Kraszna. Early 20th century

Komádi, Hajdú-Bihar County

A kind of cast fishing is also used by small fishermen, who fish alone. They weave or cut out the pöndör or rokolya net in the shape of a circle. The fisherman knows that as the fish cannot descend perpendicularly, it {241.} therefore tries to go downward sideways. The net, because of the lead weights placed along its edge, sinks faster than the fish descends. The fisherman first of all knots the rope on his left wrist. This rope, formerly made of horsehair and more recently of hemp, is attached to the centre of the circle. The fisherman then flings the net onto his left shoulder like a cloak. He puts into his mouth one part of the lead cord that surrounds the net, and holds on to it with his teeth. Then, on the shore or in the bow of a boat, he turns on his heel with a sudden motion, spreading the net evenly over the water. Because of the lead weight the edge of the net sinks faster and closes up rapidly below, so the fish cannot escape from it. This type of net is known in the region of the Mediterranean and has also reached the Black Sea, and it can be presumed that the Magyars had already become acquainted with it there.

Tiszaörvény, Szolnok County. Early 20th century

When fishing with a hook, there are usually several hooks on a single line. This is often 60 to 80 m long and kept afloat by buoys made of a hollowed-out gourd. One end is fastened on the shore, and a hook dangles at every metre length. Huge hooks were used to catch sturgeon (Acipenser Huso), which swam upstream from the Black Sea, the weight often reaching one or two quintals. At such times a rope would be set across the Danube, to which the large-sized, many-forked hooks were attached. Wooden buoys kept the rope on the surface. Sometimes the rope of the hook was fastened to a post and placed on the shore or on a raft, with a cowbell tied on it. When the fish took, the cowbell rang and brought the fisherman quickly to the scene.

Haraszti, former Verőce County

Sára, Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County

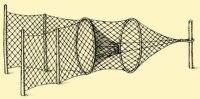

Among the innumerable kinds of nets used in Hungarian fishing, we {242.} shall mention only the kind used for fishing sweeps. The smallest example is the bicentral net, which rarely reached 6 to 8 m in length and one and one-half m in width. Two men worked with it, each holding a stick fastened to an end of the net. When they felt the splashing of the fish, they lifted it out of the net with a smaller net. Much larger than the former is the so-called old net, or by another name, large net, which is basically an enlarged version. It often extends in length to 80–120 m. Even larger than this is the drag net, which differs from the big net in that it has a sack (káta) at its end, which gathers the fish which can then be taken out together. The big net and drag net are the largest pieces of equipment used on Hungarian fishing sweeps, which they keep dry, and is repaired on the water’s edge on poles resting on huge beams. As one men cannot handle the huge nets alone, several unite their strength and labour, and sometimes jointly put in the money necessary for the equipment. The fishers share the takings in a pre-arranged way. Such fishing groups are called bokor (cluster), kötés (bond), and felekezet (sect), and are typical of Hungarian fishing. The large size and structure of the {243.} net require that every member of the group have a definite task, and everybody must obey the master or gazda. He is the one who leads the fishing, decides when it should begin and end, and defines the scope of everybody’s activity. He himself participates in fishing as a steerman. His substitute is the first apprentice, vicemester (vice-master), or kis-gazda, who pulls the bow of the boat and carries out the most difficult tasks. The number of young men is between 4 and 12, depending on the size of of the net and the extent of the water surface. If the net is owned communally, the catch is shared equally; if it belongs to the gazda, then he gets 3 to 5 shares and the men get one share each.

The Hungarian fisherman calls every section of the water and shore where he drags his net tanya and divides this territory on the basis of how many times they can cast out the net. The division of fish waters into tanyas indicated both the territory and its economic yield. Presumably the Magyars learned the organization and terminology of communal fishing before the Conquest, in the vicinity of the Eastern Slavs.

General. Early 20th century

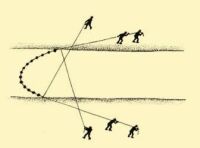

Fishermen did not rest even in wintertime when the waters freeze. They cut the thin ice with a spear, or struck at it so hard with a hatchet or wooden club that they could easily lift the dazed fish out through the hole. They even used the big net or the drag net under the ice. At such times the fisherman tied an iron crampoon on his boots, so that he could move around with complete safety. A huge entrance hole was cut into the ice, and the net was put in it. Then smaller holes were made in a wide circle, through which the cord of the net was passed with a stick. This rope went all the way to the take-out hole. This is the way of fishing wide areas under the ice, and it usually brings good results.

Vencsellő, former Szabolcs County, 1930s

{244.} The nets were knotted from hemp yarn by means of old-fashioned net-knitting needles by the fisherman himself or by his wife. The size of the mesh varied, according to the purpose of the net. There are, for example, nets with double walls, which further entangle sharp-nosed fish. The nets made by the women of certain areas were known and used far and wide.

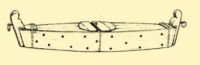

The caught fish had to be kept for a varying length of time. That purpose was served by the boat-shaped bárka (fishing ark) that had holes on the side and could be sealed on top. Formerly, it was made of reeds or wicker. Back- or hand-baskets to carry the fish home or to market were also made of wicker.

Lake Balaton. Second half of 19th century

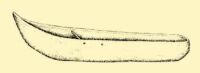

Fishermen moved on the water using various forms of boats. The oldest type was made from a single log scooped inside or burned out with embers. These were replaced by the more safely moving flat boats, constructed of planks. The large-sized nets could be placed more easily on these. Boats were directed and moved with a stake in shallower water and with paddles of different shapes in deeper water.

The characteristic vehicle of water locomotion was the raft, fabricated from wood or sheaves of reed. The former was for hauling logs in rivers and the latter to move between swamps and marshes. The ferry has served, and is still serving today, to move men and freight across rivers. These are large-sized, flat-bottomed crafts for transport, which can even take four loaded carts over to the other side at one time. They were pulled over by hand power, along a rope stretched between the two banks, taking advantage of the water current; in shallower water they were poled towards a ramp cut into the shore line.

| Hunting | CONTENTS | Animal Husbandry |