| Apiculture | CONTENTS | Fishing |

{236.} Hunting

Hunting has been a man’s job at all periods; the task of the women was the skinning and the preparing of the game. Some elements of Magyar hunting can be traced back even before the Conquest. Thus arrows with a V-shaped head were shot at water birds, because it got stuck in the reeds on account of its shape, and was then reusable. Hungarian archeologists have found a number of examples of these in graves dating from the Conquest, and the Ugric relatives of the Magyars also used such arrows until recently. Similarly, we can trace the equivalents of certain types of snares and traps back to pre-Conquest times. Anonymus, the first Hungarian chronicler (12th century), also proclaimed the importance of hunting : “Whereon in the year 884 the Magyars started out, the young men were at hunting nearly every day, and from that day until the present, the Magyars above other nations are better at hunting.”

Little Cumania (Kiskunság). Early 20th century

The new homeland offered largely the same opportunities for hunting as did the South Russian steppes. The peasantry, however, was gradually left out of it, especially in 1504 when King Wladislas gave the right of hunting to the nobility. From then on both serf and commoner were rigorously punished if caught hunting. Thus the methods of hunting amongst the peasants and the nobility developed in different directions. The latter soon turned to firearms, while the former retained the old methods which they could practise in secret, at most improving the forms and in some places augmenting their numbers.

Region of Debrecen. Early 20th century.

We wish to mention only a few of the numerous methods, procedures, and implements of hunting. The simplest and, in earlier times, the most common one was beating the game. Even in the last century wolves were hunted in this way. They chased the wolf on horseback and beat it with a whip with a wire on its end, which twined about the wolf’s neck and choked him. The largest bird of the Carpathian Basin, the huge-bodied bustard (túzok, Otis torda) could not fly up with its frozen wings when there was a freezing drizzle. At such times the entire flock could be driven into the yard of one of the peasant farmsteads with a whip and killed there for their excellent meat.

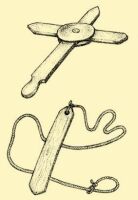

Variously shaped sticks were also used for hunting, with which they struck down rabbits or wild ducks that were too slow on the take-off from the water. Flinging sticks were made of hardwood, sharpened on both ends, and they threw it rotating towards the animal to be killed in such a way as to make the largest possible wound. The hitting stick, for a kind of lapwing (Tringidae), was made of two pieces of wood laid crosswise on top of one another, and thrown spinning among water birds that gathered at the sound of a decoy whistle.

Sárköz region. Early 20th century

The sling shot deserves an important place among hunting implements, for it is equally suited for bringing down birds and smaller game. Made of soft leather, it has another piece of leather in the middle, 6 to 8 cm wide, to hold the missile, which is made of stone or dried mud. The hunter ties one end of the leather strap to his wrist, while holding the other end in his palm. He spins the sling several times over his head, lets one strap go, and the projectile flies out with great force. In the 18th and 19th centuries even the field keepers used this weapon, with which they tried to keep away not only the destructive birds but thieves as well.

Great Plain. 1930s

{237.} Hungarian peasants used many different kinds of snares, knotted from horsehair, string, twine, or wire and placed in the path of the game. A horsehair snare was sufficient for the smaller birds. They tied 20 to 30 loops on a wooden board, on seeds which were spread and, as the bird was picking up the seeds, its neck sooner or later got caught in one of them. Similar snares, rigged up on a husked corncob, quickly trap the neck of a hungry bird. One version is the pulling snare, equally used in water and on land. They put a strong supple twig into the ground, bend it down and fasten it with a suitable small peg. They tie the end of the snare to this and place it in the path of the game. It if pushes the peg the twig is freed and the snare pulls the catch up in the air by the neck.

At one time bird-catching was practised with a net in the shape of a wide circle. Charters from the Middle Ages allude to the royal net carriers, and even note the names of a few characteristic fouling nets. Quails were chiefly caught with nets. They covered an area of grass or growing grain with it and enticed the quails by imitating their call. Once the birds had arrived under the net they suddenly startled them, and the birds, trying to fly up, could not escape. They also spread a net over the holes of foxes and badgers, so the hunted animals could not get away. They still hunt game with nets today, when trying to catch the game alive to settle them on other territories.

Smaller birds, primarily singing birds, are usually captured with liming. The necessary gluey material is usually boiled out of mistletoe. It is spread on the prominent branches, of bushes, near which is hung a call bird in a cage. The bird that comes to its call and settles on the bush is caught by the sticky bird lime.

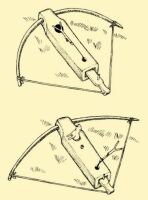

One of the oldest hunting tools traceable to the Finno-Ugric period is the bow trap, which is primarily used for catching gophers. Its most important part is the bow, led through a longish, narrow box. A flat wooden board, studded with nails on the end, goes in and out of it. With this they tighten the bow and fasten it with a small peg. The trap is placed on the gopher hole. When the animal touches it, the peg loosens easily and, driven by the elastic power of the bow, the forward sliding wooden board captures or kills the gopher. We find various versions of this trap among the hunting tribes of northern Europe and northern Asia, and certain data establish its proliferation into western Europe as well.

Great Plain. Late 19th century

The crushing trap, which killed the game by dropping a piece of wood or stone on it, was also known in many places. Today’s versions are reduced in size and are mostly used for mouse or rat traps. Formerly, using logs of wood, they caught larger predators, bears, or deer with this method.

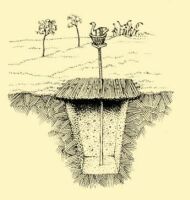

Catching game in a pit was once practised over a wide area, generally for large game. They dug pits for wild boar in the southern part of Transdanubia, using a surrounding fence to lead the animal into the pit it was thus unable to avoid. Wolf pits were longest in use in swampy, boggy regions. When the water froze, the starving wolves ventured right to the edge of the village, and often even into the yards. At such times a pit 2 to 3 m deep was dug along their regular path, and a stake or several stakes were beaten into the bottom of it. They covered the top {238.} with reeds, bulrush, or weeds, and for bait, they put a piece of meat or even a live goose in the middle of it on a long pole. The wolf, slipping by, noticed the desirable meal and jumped for it, but the weak roof broke under him and he fell into the pit where he was either impaled on the stakes or killed by the men with pitchforks.

Various methods of hunting with the help of animals was widespread. Rabbit, deer, and often wild boar were chased with a dog until the game collapsed. In the Middle Ages hunting and catching birds with a falcon or eagle was primarily the amusement of the nobility, but the peasantry practised certain forms until almost the most recent times. They would keep an eye on the nest of the osprey and fish hawk, built on trees in the swamp, and when the mother brought smaller game and fish for her young, they could take it away from them. Thus they forced the mother to bring more and more prey.

Peasant hunting, because of its prohibitions, played at most only a supplementary role during every period in providing food. Nevertheless, it was practised by everybody. There are still some specialists around today who know and practise various methods of trapping.

| Apiculture | CONTENTS | Fishing |