| Animal Husbandry | CONTENTS | Hunting |

Apiculture

Beekeeping is among the most ancient occupations of the old Hungarians, as indicated by the words of Finno-Ugric origin such as méh, bee; méz, honey; odú, bee dwelling, hole; ereszt, bee colony. 11th-century sources already mention villages and families which provided honey to their lord. In the north-eastern corner of the linguistic territory so-called stone hives have survived, dating from the same period, holes cut into the rock for keeping bees. A number of names of villages–Méhes, Fedémes (bee-house)–testify to significant apicultural activity over most parts of the linguistic territory from the 11th to 13th centuries.

Domaháza, former Borsod County. 1940s

The most primitive form of apiculture has the character of food gathering. The apiarist goes out to the edge of the forest and captures, in a vessel made out of horn or wood, bees sucking flowers. When enough of them are buzzing inside the vessel, he lets one out and watches the direction of its flight. He follows it as long as he can see it. Then he lets out another and follows it also. He repeats this procedure until he arrives at the hollow tree where the bees live. Then he closes up the tree, kills the entire family with smoke and takes away the honey.

Györgyfalva, former Kolozs County. Early 20th century

It also happened that they did not kill the bees but left them in the tree and took the honey from them only from time to time. In such cases, a property sign was carved on the trunk of the tree, and a wooden board was fastened in front of the hive and a hole bored in it for the bees to get in and out. When they thought that enough honey was collected, they removed the wooden board, smoked out the bees, and took away the {233.} honey. They always left enough in the hive for the colony to survive until spring. While live tree apiculture was not known to have existed in the Carpathian Basin according to former literature, more recent research has found it in several places.

Bees could be actually cared for only if they were kept in one place and in the apiary. Apiaries were erected in peaceful, quiet spots, so that no one should disturb the diligently working families. Thus apiaries were often set up in a forest, on certain islands in swampy areas, but most frequently an area was separated off within the settlement in a fenced part of the garden. The simplest are the bee gardens, surrounded by a fence, where the hives stand on the ground or on low legs. Walls, usually made of wattle, surround the fenced apiaries on all sides. They run a half-sided roof all around inside it, under which the hives (köpü, kas) sit on shelves, facing into the yard. The advantage of this arrangement is that it is easy to close the hives off from the outside world. Drinking water is placed in the centre of the yard, while the beekeeper generally lives in the hut attached to the outside of the structure. This form, called kelenc, can so far be shown to have existed only in the north-eastern part of the linguistic territory. Most widespread are the partly roofed apiaries, on the wooden boards of which the openings of the bee dwellings face towards the south-east. One section of these consists of a shed that provides only a little protection against the rain, but most such sheds are surrounded on three sides by planks and wicker walls, and in this enclosed area the smaller tools of apiculture are kept.

Vajdácska, Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County

Komádi, Hajdú-Bihar County

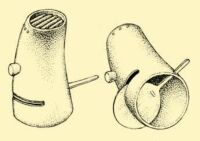

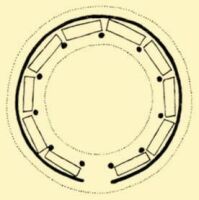

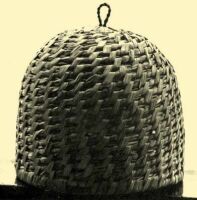

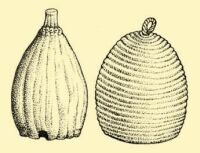

{234.} In forested regions, the bee dwellings are called köpü, carved or burned out of logs usually hollow inside. These wooden hives are often richly ornamented with carvings. In forest-poor areas, hives called kas are woven out of bulrushes or straw, and their size and shape vary by regions. In other places they cut down a willow tree at the same height as the beehives and split it into several forks. They force these apart and weave them around with supple branches. Afterwards the branches are plastered with clay mixed with cow dung which provides good protection for the bees in the winter. During the winter a bulrush or straw cope is put over the hives in the western part of the linguistic territory, so that they do not have to store them in covered areas. The bee dwelling called kaptár, made mostly out of planks after western examples, gradually eclipsed the traditional hives from the second half of the last century, which still have survived sporadically until today.

Former Szatmár County. Early 20th century.

1. Fluting out the interior. 2. Preparing the hive through burning out the interior. 3. The prepared hive and its construction. 4. Honeycomb. 5. Planks for the hive

a) Made out of wicker and plastered. Transylvania. b) Woven out of bulrush. Former Borsod County. First half of 20th century

{235.} One of the great events of beekeeping is the flying out in spring. According to folk belief, the time must be selected carefully, because bees are weak on Monday and Saturday, and become envious and quarrelsome on Tuesday, Friday and Sunday. Therefore most people recommend Wednesday or Thursday, because then the bees will be strong and diligent all through the year. But to make them really tame it is thought necessary to pass them through the wool of a white sheep, well washed with sand, when they first leave the hive in the spring. The beekeeper who preferred his bees to be quarrelsome and thieving would pass them through a wolf’s windpipe, or smear the opening of the hive with rooster blood. Thus the bees defended it against every intruder.

In the summer, the swarming of the bees begins when the new family gathers and tries to find a new home at a distance. At such times beekeepers try to bring the swarm to a stop by cracking a whip, clattering, spraying water, and throwing pieces of clothing in the air. If the bees settle on a tree, they then fasten a hive on a long pole and shake them into it, carry them back into the apiary, and settle the family in a permanent hive.

For a long time in Hungarian peasant apiculture they kept the swarm for the next year but smothered the mother family with smoke and then took the honey away from them. Later on they covered the full hive with another hive and the beekeeper kept beating the bottom one until the bees, annoyed by the noise, moved into the top hive. Thus they could take away the necessary amount of honey without destroying the family. In the autumn honey merchants (barkács) appeared, who took out the honeycomb along with the honey, stuffed it into barrels, and carried it to the market.

Honey as a sweetener played an extraordinarily large role in the Hungarian peasant kitchen, and earlier it was also used in the diet of the nobility. It is the indispensable basic material of honey cakes, but nectar is also made from it. The wax was primarily used for candle making. As these functions were curtailed beekeeping decreased significantly, yet even today, along with modern apiculture, the traditional peasant procedures of beekeeping can be found in every village.

| Animal Husbandry | CONTENTS | Hunting |