| Foraging | CONTENTS | Animal Healing |

Branding and Guarding

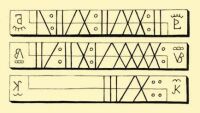

Animals were marked primarily by branding. The branding iron (billyogzó) is an iron implement with the head shaped in the form of the initials of the owner or, in the case of a larger community, its identifiable sign (cf. pp. 65–6 and Figs. 4, 5). It is made red hot, and used to brand the rump of the animal, or, in the case of sheep, they smeared paint on it making a mark in that way. The mark was not for the benefit of the herdsman, who could tell every single member of the stock entrusted to him anyway, but for the owner. Animals change so much from spring to autumn that the owner does not always recognize it and can identify {260.} his own only with the help of the branding mark. Branding, therefore, provided a check on the herdsman and also helped to find and identify stolen stock.

At a primitive level, any piece of hot iron is sufficient for branding an identifying mark. Thus they burned =, V, or + signs into the back shoulder blade of the animal with a plough iron, a coulter. The branding irons of more prosperous farmers, passed on from father to son, were known and kept track of far and wide. Special marks differentiated the common stock of the village or town.

Smaller animals were not branded but marked by nicking. Thus bits were cut off the ears of sheep or marks cut into them. Around Kecskemét, the special mark of every larger sheep-keeping family was generally known. For example, sheep belonging to the Deák family were marked on the left ear with the shape of an arrow, and a piece in the shape of a swallow’s tail was taken out from the right ear of the stock of the Szappanos family. For geese and ducks, the various marks were cut into the webs of the feet.

The stock carries such differentiating marks through its entire life. However, there are also temporary marks. Thus the shepherd carves small marks out of wood, one larger, the other smaller: two small-sized sickles, locks, chairs, violins, etc. and fastens one on the neck of the mother, the other on the neck of the lamb, so that at nursing time kinship can easily be recognized. When mother and young get used to each other, the shepherd removes the marks and puts them away for next year.

Great Plain. Second half of 19th century

Debrecen, 1920s

The head shepherd took account of the stock that was handed over to him by notching. This is the counting method, the way of keeping a check, used by herdsmen who do not read and write. With it they could always check the number of the animals entrusted to their hands. They mostly used the half or paired notching, by notching the number of the animals on a stock, then splitting the stick in half. One half stayed with the herdsman, the other with the farmer. They did the splitting in such a way that the marks could be read separately, but if the two halves were placed together it was immediately possible to see any change. New births were recorded by the herdsman on the stock notching (tőkerovás), deaths on the carrion notching (dögrovás). The expression “dögrovásra kerül”, be destroyed, perish, and “dögrováson van”, to be on one’s last legs, was taken over from the vocabulary of the herdsmen.

Hortobágy, former Hajdú County. 1920s

Debrecen. 1828

The dog is always the herdsman’s faithful helper in shepherding, {261.} keeping together the stock, but there are other means of making the often very difficult job of guarding easier. Among these the cowbell, bell, and rattle deserve principal place. These are hung on the animal’s neck and can signal its whereabouts, or can help the lead animal to direct the entire flock. The cowbell is made of plate iron, bent into shape and soldered together with copper (cf. Ill. 44). The more copper used, the more pleasant its sound becomes. We find many versions ranging from almost half a metre in size to a few centimetres, the latter worn on the neck of the sheep. These are the well-known products of certain regions, but some gypsy clans also make them with a great deal of expertise. The bell is actually a reduced copy of church bells. It is cast from copper to which a little tin or perhaps silver is added. A good price had to be paid for large bells that had a beautiful sound, and on some occasions certain exceptional specimens were exchanged for a young head of cattle. Cowbells were mostly tied on the necks of cattle, occasionally a bell was put on an ox, and only bells were put on horses. The rattle is a metal ball of small size with an opening cut on its lower end. Iron pellets shaken inside it give the clattering, rattling sound. It is generally tied on a sheep, a pig, or maybe a dog. Rattles are tied on a horse only when it is hitched onto a sled during the winter, at which time the rattles are used alongside and carefully synchronized with the bell, so that people coming from the opposite direction could take notice of and avoid the quietly gliding sled.

Karcag, Szolnok County. 1787

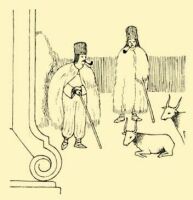

The stick is the most important among the hand tools of herdsman. All use it with the exception of the horseherd. Most herdsmen made the stick themselves, but specialists particularly skilled in the craft can also be {262.} found. Oak, dogwood, plum, or wood from the pear tree is preferred for the basic material. They often notch it with a jackknife while it is still live on the tree so that it grows scabrous. It is cured for a long time, often even put under the manure heap to develop the suitable colour. Its sheen comes from rubbing it with lard. Herdsmen not only shepherded with the stick, but formerly it also served as a good throwing weapon against wolves. Holding it between his legs, the herdsmen could even sit on it. When he pushed it into the ground and threw his cloak on it, the makeshift tent would offer a little shade in the scorching Great Plain sun. Shepherds of Transdanubia carve a hook at the end of the staff, while shepherds of the Tiszántúl cast the crook from copper. They not only shepherd the animals with it, but by hooking the hind leg of the sheep, can easily select the one wanted. The swineherd used a hatchet with a handle that was approximately one metre long. This was not only an excellent defensive weapon, but was also used to kill the piglet that was destined to be eaten and to cut mistletoe off the tree for the stock.

Hortobágy, former Hajdú County. Early 20th century

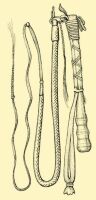

The whip is always short handled and is the inevitable tool of every herdsman except the shepherd. Straps are split into narrow ribbons, then braided around a hemp rope into 6, 8, or 12 strands, and smoothed into a handsome rounded form by wetting. A wider strap goes on the end, to which they tie a lash made out of horsehair. The whips of horse and cattle herds are lighter, and those of the swineherds heavier, because they even braid wire into the lash, which in turn is fastened to the handle not by a strap but by a copper ring. Driving the stock is done not only by flicking the animals with the whip, but also by cracking it to make loud sounds like gunshots, which tell the flock the direction of the drive.

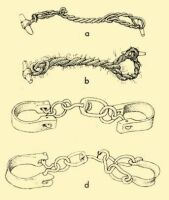

a) A fetter made out of hemp-rope. b) Out of rope, hemp mixed with horsehair. c) Out of wood. d) One end is wooden, the other iron. Szentes, Csongrád County. Second half of 19th century

A hobble (nyűg or béklyó) is put on an animal that grazes alone or in smaller groups and on the horse the herdsman constantly uses, so that it cannot wander far. The nyűg is made of horsehair or hemp, and with it two of the horse’s legs are tied together, or perhaps the opposite fore and hind legs of two horses are linked, so that they can graze slowly but have no chance of running away. The simpler form of the béklyó was carved out of wood. The blacksmith makes it of iron and puts a lock on it to try to prevent theft. The hobble is closely attached to the horse’s pastern, its short chain allowing only small steps. According to a herdsmen’s superstition, even a well-designed hobble can be opened with a plant called vasfű (iron grass), which is why they searched for it everywhere from spring on.

A wooden board is hung before the eyes of a wild bull or cow, so that its range of vision is restricted. A ring is put into the pig’s nose so it cannot root up the yard and wreck the pen. Cattle and bison are led by a ring hooked into their nostril. The clog hung about a dog’s neck curtails it in its movement to such a degree that it cannot wander far off.

Hortobágy–Tiszacsege, former Hajdú County. 1930s

The herdsmen were most afraid of stampedes of the herd. The most generally-known method of producing one was to burn hat-grease or cow hooves, the smell of which makes the stock wild, so that they cannot be prevented from bolting, and gallop away. Stampedes also happen when the stock can no longer bear the stinging of flies and try to escape the pain by bolting (bogárzás). There were stories about some herdsmen who possessed knowledge by which they could make the {263.} herds of others stampede, whilst still protecting their own from every danger. Related superstitions are known primarily in the Great Plain and belong among the oldest Hungarian folk beliefs.

Vukmaroca, Slavonia. Around 1910

To catch an unbroken animal out of the herd was a very difficult task. Horseherds used a lasso or, by a word of Cumanian origin, an árkány (lariat) (cf. Plate IX). They herded the horses to the well, then the herdsman approached the selected horse, scared it, and, when its head was stuck up, threw the loop over it. He held the lariat until one of his mates put the halter over the horse’s head. Hungarian grey cattle were caught in a different way. They fastened a loop at the end of a long pole and tried to cast it over the horn and down to the base. They wound the {264.} rope that subdued the wild animal on the well-sweep, but the frantic animal often had to be pressed to the ground by a cart ladder until it wore itself out.

| Foraging | CONTENTS | Animal Healing |