| Buildings for the Stock and Herdsmen | CONTENTS | Alimentation |

Breaking in the Stock and the Means of Transportation

One of the greatest values of livestock (cattle, horses) is that, hitched to the yoke, they plough the land, haul in produce, drive the dry mill, carry finished or half-finished products to the market, and do many other such tasks of basic importance in peasant farming (cf. Ill. 138–40). This is why draught animals were broken to the yoke with a great deal of care and by a well-defined method.

Vista, former Kolozs County

Hollókő, Nógrád County

In the case of unbroken animals driven to pasture, the calf usually stayed with the mother. A young herdsman selected one of these calves, to become a draught animal and tied it to a stake near the farmstead. Its mother nursed it when the herd returned from the pasture. They gave it more rope after weaning, so that he could graze around. It thus became used to the herdsman. Such pre-training is unnecessary in the case of domestically kept animals. Young bullocks were broken in at three years of age, generally in the autumn, less frequently in early spring. It was hard, despite the previous training, to extract the selected young animal from the wild herd. When it had quietened down, they led it, tied {271.} behind the cart, into the yard of the farmstead or village dwelling, and there they tied it to a tree. They put neither food nor drink in front of it, but kept offering it to the animal. If the animal accepted it, it was becoming tame, and they could start breaking him to the yoke.

Tiszabercel, Szabolcs County. 1930s

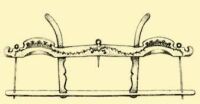

The yoke (járom or iga) is a frame of wood, into which two oxen can be hitched next to each other. They put this around the ox’s neck and close it off on the side by the yoke pin, usually made of iron, so that it cannot pull his head out. In the yoke the ox pulls along the centrally placed shaft by the strength of its neck and withers. The end of the pole is fastened to the cart or the forecarriage of the plough by a thick pin. Several pairs of oxen are connected consecutively by means of poles. This kind of carriage is always driven with a long-handled whip, usually made of rope and capable of reaching to the first pair of oxen (cf. Fig. 121).

Debrecen. First half of 19th century

The young bullocks selected for breaking in are first matched according to size and by the shape of their horns. After that comes the attempt to put their necks into the yoke, which is usually such a difficult task that it requires the strength of several men. Once this has been done, they are hitched before and behind already trained, older pairs of oxen. The training is mostly done with a cart, whose wheels are tied in place, or perhaps making them used to work by ploughing or harrowing. If one of the young bullocks continually tries to break out of the yoke, they try to break him with the spiked tinószoktató (bullock breaker), that is pulled onto the yoke pin. Months pass before the animal learns to do every kind of work and understand the words that signal starting, stopping, and turning, and it finally becomes an ox.

Great Plain. Late 19th century

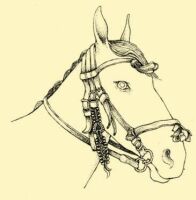

Breaking in a horse also starts with catching it. To do so a rope (pányva) is thrown on the neck of the selected horse, but as it tries to get loose by every means, it takes three to four men to control the animal. When it tires, they put a tether made of hemp over the horse’s head, and the saddle on its back, then the bridle and the bridle bit. After this the most able, venturesome young herdsman can start to break in the horse.

Bugac-puszta, former Bács County. 1930s

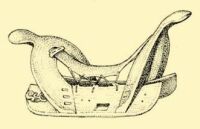

The Hungarian saddle is extremely simple, composed of four pieces {272.} of wood. Two longish wooden plates fit closely and directly onto the horse’s back, with the pommel carved in the shape of a half circle, fitting into the place and holding them together. Leather is stretched over the projecting parts. This form of saddle is completely different from the one built on a Λ-shaped wooden base in the western part of Europe.

We can find related kinds in the East, and the Finno-Ugric origin of the word for saddle, nyereg, itself implies a long past. The Hungarian saddle assures much easier movements for the rider, and especially for the horse, a fact which confirms the military successes of the Magyars at the time of the Conquest. Beginning in the 18th century, this saddle form was also naturalized in the west with the troops that were set up on the pattern of the Hungarian hussars.

Debrecen. First half of 20th century,

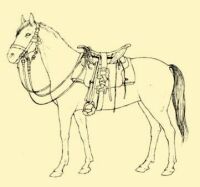

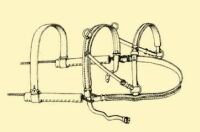

When the horse is sufficiently obedient under the saddle, it can be put in harness. They use the breast harness throughout the Hungarian linguistic region. Only with the introduction of the western, cold-blooded horses did the collar harness spread on the larger estates and in the western section of the linguistic territory. Two horses are generally harnessed to the pole, but occasionally a third horse pulls the cart from the right. Four horses are hitched in pairs in line ahead, while in the case of five, the two behind and the three in front really make the cart fly. In these cases the driver often drives from the back of the left rear horse and directs and urges on those harnessed in front with his long whip.

At first they made a young colt pull a tree stump, and when he was used to doing that, they hitched him in front of the cart as the third horse, the lógós (trace horse). When he no longer misbehaved, the colt was made, along with the mare his mother or another older horse, to serve as the nyerges or rudas, the left or right hand horse, depending on the position that best suited its size.

Galgagyörk, Pest County

Drágszél, Bács-Kiskun County

{273.} The simplest means of conveyance are the sleds, which slide on the ground or on snow. Hay is hauled on a sled, and certain types of husbandman’s buildings are erected on them (Transylvania), as well as wicker granaries, which can thus be dragged farther away from where they stood (the Southern Great Plain). Recently sleds are used only to draw on snow. The short Székely bakszán was used to transport timber logs, fastened on one end to the sled. In Upper Hungary, two such sleds accommodated the length of wooden logs. There is also a form of sled in general use over a large part of the linguistic region which slides on two runners having upright fronts to which are fastened cart-like sides or maybe a wicker frame which suits for carrying a load or people.

Debrecen. Around 1940

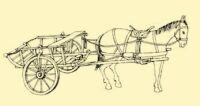

The simplest forms of vehicles on wheels are two-wheeled, and drawn by a horse, more rarely a donkey. Herdsmen used such carts to carry their equipment and food from the settlement to the pasture. The talyigás (barrowman) of Debrecen and Miskolc was the haulier for the poor, while navvies carried soil to the designated area at the time when the great works of regulating the rivers and building the railways were going on, beginning in the second part of the previous century. A wooden box-body sits over the spoked wheels. Between the double shafts, which are continuations of the side-beams for the bottom of the cart, they hitch one horse and so can haul a considerable load. One version of this, mounted on springs and serving to transport people, is the tumbril (kordé), which even spread into towns (Nyíregyháza).

Miskolc. It sometimes occurs even today

Debrecen. First half of 20th century.

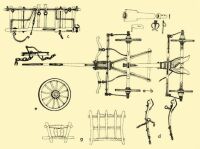

a–b) The lower framework of the wagon. c) Its sides. d) The woods for holding the sides in place, called “lőcs”. e) A wheel. f) The axle. g) The front and back rack

Jászjákóhalma, Szolnok County

The most common form of wheeled transport is the wagon, which is fairly uniform over much of the Carpathian Basin. It may even have originated by connecting the two-wheeled carts, for even today most {274.} wagons can be taken apart into two sections, or, with the aid of the stretcher that runs centrally along their bottom, can be adjusted to the required length. The difference between horse- and ox-traction comes from the fact that the horse pulls by traces, the shaft only serving to give direction, whereas the ox transfers its draught power directly through {275.} the pole. The front two wheels can be turned as required around the centre pin until one hits against the lower plank of the wagon body. The rear wheels cannot be turned. Nowadays the wheels are equal in size, but formerly the wheelwright made the rear wheels larger. The wheels consist of four, five or six felloes, with two spokes mortised into each, so that the wheels have eight, ten or twelve spokes.

Nyíri, former Abaúj County. 1950s

The difference between the wagons of the Great Plain and those of the mountain region lies not so much in construction as in size and fittings. The former are much shorter and are equipped with a vendégoldal (frame), so that more can be loaded on them both in width and in length. Otherwise wagons are lined with a wicker frame, suitable for carrying corncobs or other produce. The vehicle of the mountain region is significantly longer, and its high and latticed sides make loading easier. Because the roads vary in quality they cannot load it high.

Originally the coach (kocsi) must have been a version of the wagon. It got its name from Kocs, a town in Komárom County, which during the Middle Ages was one of the most important stations on the highway that connected Buda and Vienna. They called the light vehicle made here kocsi-szekér, which later served almost entirely to transport people. The entire mechanism, and along with it its name, spread into Western Europe (English: coach, German: Kutsche, Swedish: kusk, Italian: cocchio, French: coche, Spanish: coche). In the course of later development a spring- or suspension-framed, carriage-like vehicle evolved from it.

The wagon is not only indispensable to the peasant, but from the Middle Ages on, it was the most important means of transportation and commuting that served to exchange the products of various regions. In the towns and villages, the carters, possessing the equipage and vehicles, formed a special social group. Certain villages occupied themselves almost exclusively with hauling. Thus, for example, the hauliers of Tokaj-Hegyalja carried wine to Poland and Russia, and brought back furs, clothing material, and special food-stuffs. The carters who carried farm implements, lime, and charcoal to the Great Plain returned loaded with grain. The hauliers carried the products of potters, weavers, and furriers to markets. Therefore they played a significant role not only in spreading news, but also in disseminating products and cultural goods. The mail coach by and large just carried people, so that its importance lay in spreading news and in carrying the post.

| Buildings for the Stock and Herdsmen | CONTENTS | Alimentation |