| Animal Healing | CONTENTS | Breaking in the Stock and the Means of Transportation |

Buildings for the Stock and Herdsmen

We have already dealt with buildings raised within the settlement for the stock and for the fodder. We will now give an account of the temporary structures that were renewed annually, and by which they tried to protect, at least to some degree, the men and animals on the pasture from the rigours of the weather, and to keep the stock together.

Orgovány, Pest County. 1930s

The herd that wintered outdoors needed protection not so much against the cold as against the wind. Therefore they drove them for the night close to the forest, into the curve of a bank, or to a river bed, where they could find some shelter. In completely flat areas, they set up a wind screen made of reeds (szárnyék). This branched off in several direction, so that the stock could always find a sheltered side. For sheep, they just barely dug the ends of the reeds into the ground, and folded the reed wall at two or maybe three places. However, they set the windscreen for {265.} horses and cattle on top of a high earthen mound, because in this way the animals were unable to knock it over.

Gyimes, former Csík County

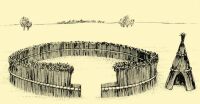

Most structures were used to keep the stock together and to protect them from predators, which is why there was no roof above their walls. The simplest form was circular, made of branches, for the pigs masting {266.} on acorns. They closed off the entrance with round timbers or by a makeshift gate. Thus the herdsman could sleep peacefully, for his herd was not threatened by the dangers of wandering away or being attacked.

In the Great Plain they fenced off the place to lodge sheep at night, using wicker hurdles fastened to stakes. These were moved from pasture to pasture and then set up again. This was done regularly on fallow land, moving each or every other day, so that the stock would fertilize all parts of the land with their night manure (kosarazás). They made such enclosures for horses, cattle and sheep out of round timbers of various sizes. In the former two instances these were permanent fixtures, the stock always being driven back from the surrounding pastures. In the latter instance they were continually moved, according to the pastures. They call the latter esztena in the eastern part of the linguistic region, while the narrow section where they let the sheep pass through for milking is designated by the word esztrenga. Since both names came from the Rumanians, we can look upon this as one element of the Wallachian influences manifested in shepherding.

There were also covered structures on the pasture, usually open on one or another of their sides, or sometimes open all round. In front of them they usually frame up a corral (karám), made of beams, spars, or reeds. This kind of corral, called akol or állás (pen), is the main provision for the protection of the livestock. Because the merino sheep cannot bear the cold nor spend the night under the open sky, they raised a sheep-fold (hodály) for them, a roofed building closed even at the sides. These, made out of the traditional building materials (soil, reeds, etc.), appeared only during the first half of the 19th century.

The pig herds required the least protection. The undomesticated sow farrowed in a pit which she dug herself, or which might be artificially deepened for her. At the bottom of this the piglet grew in safety until it gained strength and could be let free.

Karcag, Szolnok County. Early 19th century

Szék, former Szolnok-Doboka County

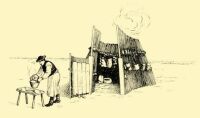

The shepherd who lived outdoors required protection, like his stock, and the structures for this purpose were formerly just as simple as those for the stock. Many shepherds did not build any kind of shelter or place {267.} of relief for themselves. For them only the sheepskin coat (suba) provided some protection from early spring till late autumn. That is why they were called gúnyás pásztor, herdsmen with garbs. They mostly carried their simple equipment from one place to the other on the back of a donkey.

Bene, Little Cumania (Kiskunság), Bács-Kiskun County. Early 19th century

The simplest structure is the windbreak (szélfogó), a reed hurdle that can be propped up at one side and under which the herdsman can put his more precious belongings and seek shelter in pouring rain. It was made {268.} of wicker, later of wooden planks, and was turned in the direction from where the rain or sun hit the strongest.

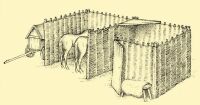

It was possible to transport a considerable part of the herdsman’s buildings. Such, for example, is the wattle fold (cserény) used between the Danube and the Tisza. At first it was woven of wicker panels. Its ground plan is square, to which was often added a wing, fenced on three sides. Here they tied the horses that were used all the time. One corner of the wattle fence was covered and there the shepherd kept his garbs, his chest, and various smaller belongings. The height of the wattle fence permits the herdsman, when standing up, to look out and keep his eye on the stock. At first only half of it was covered, later on it was covered completely so that it would give the greatest protection against the weather. Thus it slowly became a hut, a permanent structure, which remained mostly on the same spot through the entire year. Originally, the wattle fence was the most characteristic shelter of the herdsman on the move; when the stock had grazed up the pasture and moved on, the herdsman could set it up again on the new pasture.

In certain areas of Transylvania and in the central part of the Tiszántúl, they used huts on wheels as shepherd’s dwellings. They were rectangular in shape and rolled at first on solid, then later on spoked wheels. The sides and saddle-shaped roof structure were covered with planks. With animals hitched to them, they could be moved even on trackless land. The origin of this type of building can probably be looked for on the migration routes of Wallachian herdsmen, and we can trace its contacts in the Balkans as well.

Hortobágy, former Hajdú County. Around 1920

Csíkszentdomokos, former Csík County

Among the buildings that were harder to move and were usually renewed only annually, the vasaló of the Hortobágy merits mention. This is the shelter and kitchen of the herdsman, and a store for his clothes. It is circular, and made of reed walls which lean inward, but do not meet at the top. The head herdsman’s larger chest is placed across the entrance, and the young herdsmen’s smaller chests are lined up to the right of the entrance. Several footstools are also found inside, while many spoons, forks, knives, awls, and other tools useful to have at hand are stuck behind the hem of the reeds. An open fire burns in the centre, {269.} and on this the herdsmen’s boy (tanyás) prepares the cooked food. The herdsmen of the Hortobágy are so attached to the vasaló that they build it even beside their permanent hut, but in this case they only use it for cooking.

One of the most characteristic herdsman buildings is the circular kontyos kunyhó (rick-shaped hut), up to four or five metres in diameter. A door is generally left on its southern side, with a panel of reeds or, later on, of planks. Inside, there are sleeping places and chests, and smaller tools are placed on its inward leaning wall. They never light a fire in this type of hut, but rather cook in front of it. The swineherds who were masting the pigs in the winter also built round huts, but out of split logs. They laid straw, then soil or perhaps sods, on the notched structure. They lowered its base and in some places made benches suitable to lie on. A fire burned in the centre, the smoke passing through the door or through the small opening left in the roof. By means of material and linguistic evidence, current research can trace the past of this form of hut back to the Finno-Ugric period.

After the time when the territories of the pastures had been consolidated, the buildings also became permanently located. Herdsmen’s huts were already by this time generally built of mud or adobe, their roofs being of saddle shape and covered with reeds or straw. Usually such huts are located near the pens and corrals.

The Great Plain herdsmen often used the guard’s tree (őrfa, állófa). This is a topped tree with branches, 5 to 7 metres high, which they dig into the ground near, or in front of, the but or wattle fence. The functions of such a tree are many. The herdsman climbs up on it to signal to his mate in charge of the flock grazing at a distance, or perhaps to watch the movement of the stock. Cattle rubbed against the tree and polished it completely, hut at the same time left alone the easily damageable structures made of reeds or wicker. The herdsmen hung knapsacks on the tree or the raw meat that was to serve as a meal. In earlier times it was also looked upon as a sign. Only the head shepherd could use the land for grazing where he had it dug into the ground. At {270.} times, in the region between the Danube and Tisza, it was placed on different sides of the wattle fence so that the stock that lay around it would fertilize every area.

| Animal Healing | CONTENTS | Breaking in the Stock and the Means of Transportation |